NASA Stennis Flashback: Shuttle Team Achieves Unprecedented Milestone

As chief of test operations at NASA’s Stennis Space Center, Maury Vander has been involved in some long-duration propulsion hot fires – but he still struggles to describe a pair of 34-minute space shuttle main engine tests conducted onsite in August 1988. “When you stop and think about it, …” Vander begins, then pauses. “In […]

4 min read

Preparations for Next Moonwalk Simulations Underway (and Underwater)

As chief of test operations at NASA’s Stennis Space Center, Maury Vander has been involved in some long-duration propulsion hot fires – but he still struggles to describe a pair of 34-minute space shuttle main engine tests conducted onsite in August 1988.

“When you stop and think about it, …” Vander begins, then pauses. “In 34 minutes, I can leave work and drive home to Slidell (15-20 miles west in Louisiana) and be relaxing in my recliner in that amount of time.”

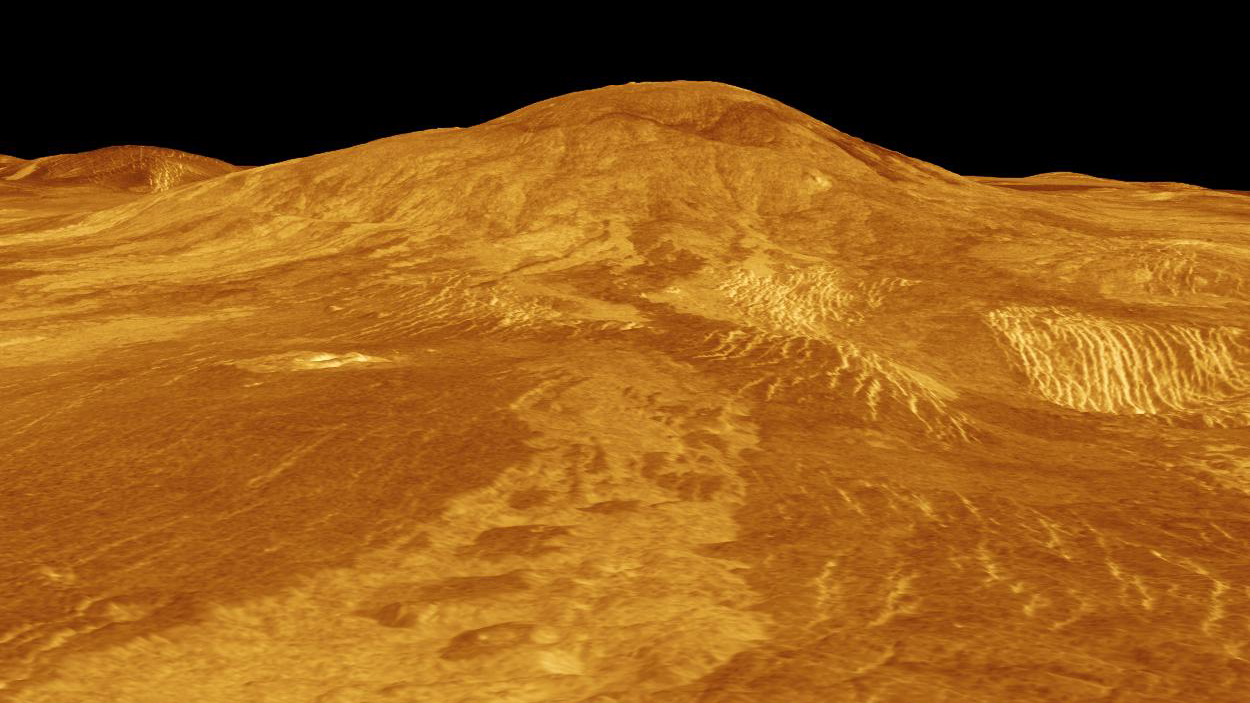

Vander’s struggle is understandable when one considers the numbers. On Aug. 3 and Aug. 15, operators at the Thad Cochran Test Stand (B-1) at NASA Stennis near Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, fired a space shuttle main engine for a total of 2,017 seconds each day, more than four times as long as the engine fired (500 seconds) during a typical space shuttle launch.

In terms of propulsion firings, nothing else comes close. The next-longest duration appears to have occurred in 2001, when a Progress M1-5 engine was fired for about 22 minutes to help deorbit the Russian space station Mir.

Vander still wonders at the south Mississippi feat. “The ability to juggle the type of challenges seen over the course of 30-plus minutes is amazing,” he said. “And you are not talking about 21st century technology either. You are talking about rather simplistic stuff not far removed from the 1960s, so there was an art to operating that type of equipment. But, they pulled it off.”

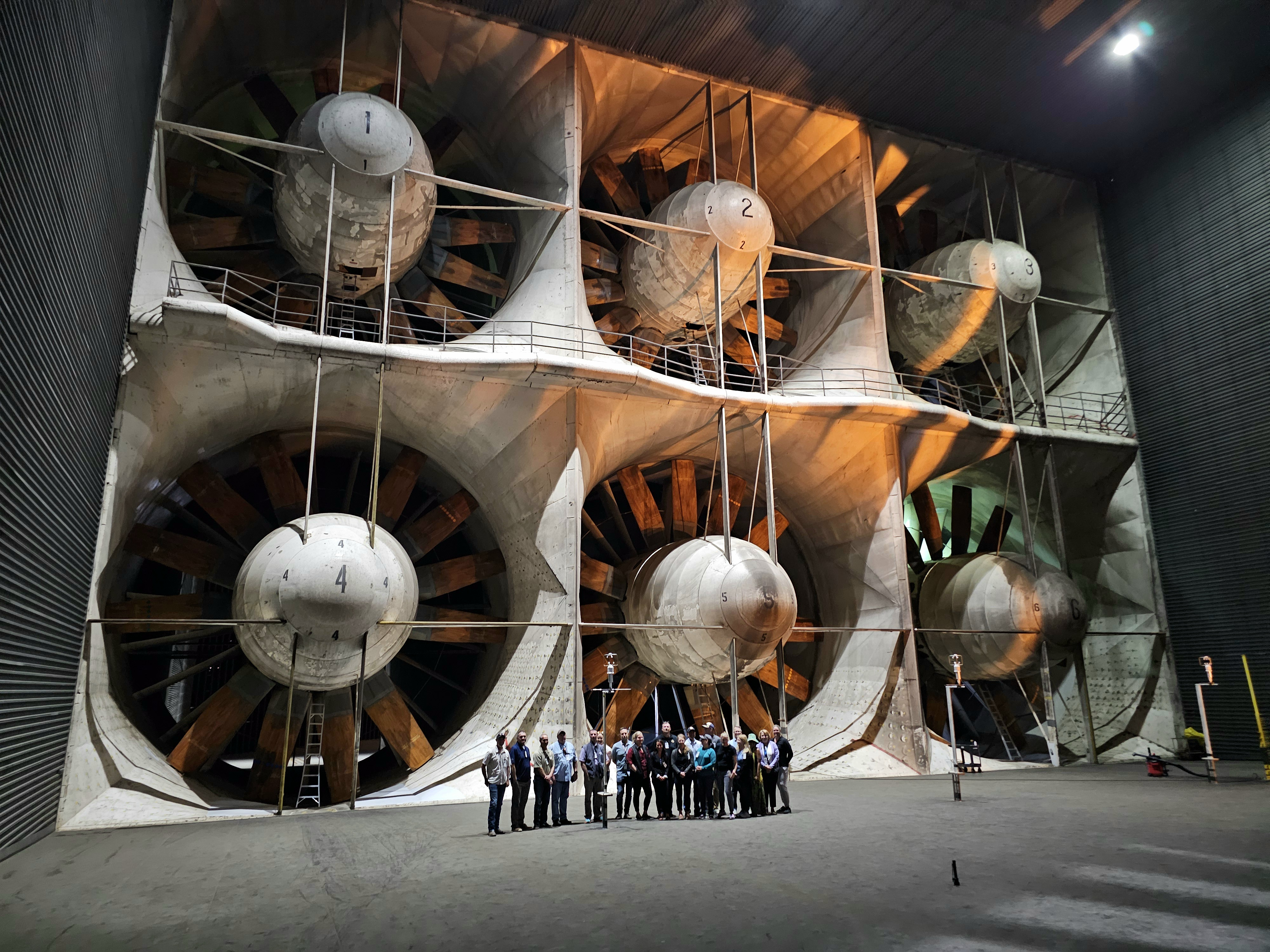

NASA Stennis may have been the only place such a firing could have been conducted.

It had the needed test facility. The Thad Cochran (B-1) stand featured a larger liquid oxygen tank to support the test and was equipped with a diffuser that allowed operators to throttle the engine to lower power levels, thus conserving fuel. The stand also had a larger dock area for additional propellant barges needed for test support.

Each 34-minute test required about 600,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen and 230,000 gallons of liquid oxygen. Careful coordination ensured proper propellant flow from barges. “We still had old pumps for the barges, as opposed to the new ones that have variable drives to help control flow,” Vander noted. “The pumps back then were basically on/off pumps. If they were running, they were pretty much running wide open. That posed a challenge for controlling flow. It was a real art to orchestrate everything for such a long period of time.”

In addition, the NASA Stennis High Pressure Gas Facility had to ensure proper volume and flow of gases to support the tests. Teams at the High Pressure Water Facility had to manage uninterrupted flow from the 66-million gallon reservoir to the test stand. “All of these were challenges they had to think their way through and logistically make happen,” Vander said.

The test team had to maintain constant vigilance of such operations. “You are always monitoring, trying to figure out what could go wrong,” Vander said. “At any given moment, you may have to react and deal with a problem. To think of those people sitting in front of computer screens, gauges, and such, watching and making sure their responsibilities were covered for 30-plus minutes, is just amazing.”

The teams were driven by a compelling factor. The nation was just recovering from the Challenger tragedy of 1986. Space shuttle Discovery would launch NASA’s return to flight in late September. Space shuttle Atlantis was scheduled to launch later in the year, but there was an issue with the fuel preburner injector on one of the engines. To resolve the matter, operators needed to record 8,000 seconds of hot fire on the injector. They decided to compile the time as efficiently as possible.

By the conclusion of the Aug. 15 test, just 340 more seconds of testing was needed to resolve the injector issue. As it did throughout the shuttle program, NASA Stennis teams delivered on propulsion test needs, resolving the issue to clear Atlantis for launch in early December.

From 1975 to 2009, the center tested every space shuttle main flight engine and all engine upgrades, and also helped troubleshoot various performance issues. NASA Stennis now tests the RS-25 engines produced by Aerojet Rocketdyne, an L3Harris Technologies company, to support launches of NASA’s SLS (Space Launch System) rocket on Artemis missions to the Moon and beyond.

“The people were proud of the work they did, yet humble,” Vander said, looking back at the record of the shuttle era. “You had to pull some of the stuff they did out of them when you were talking with them. Once they opened up, though, there were all kind of lessons there that we are still building on today.”

For information about NASA’s Stennis Space Center, visit:

Share

Details

Related Terms

What's Your Reaction?

.jpg?#)