Mental Well-Being in Space

Science in Space: August 2024 Life on the International Space Station is quite different from life on the ground. Crew members experience multiple sunrises and sunsets each day, spend their time in a confined space, have packed schedules, and deal with microgravity. These and other conditions during spaceflight can negatively affect the performance and well-being […]

4 min read

Preparations for Next Moonwalk Simulations Underway (and Underwater)

Science in Space: August 2024

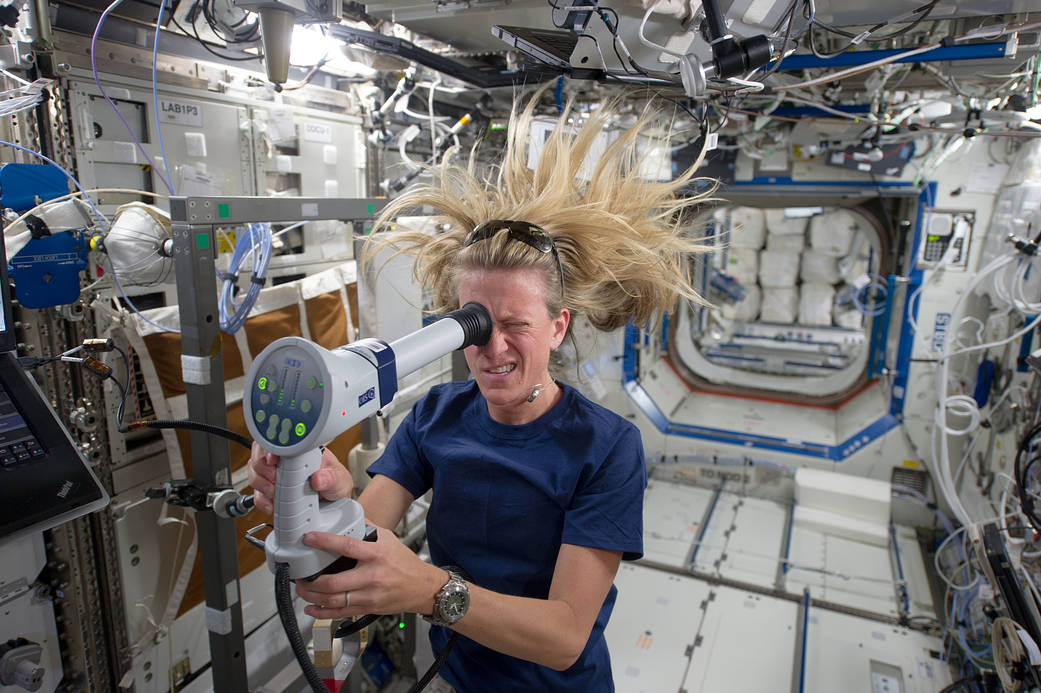

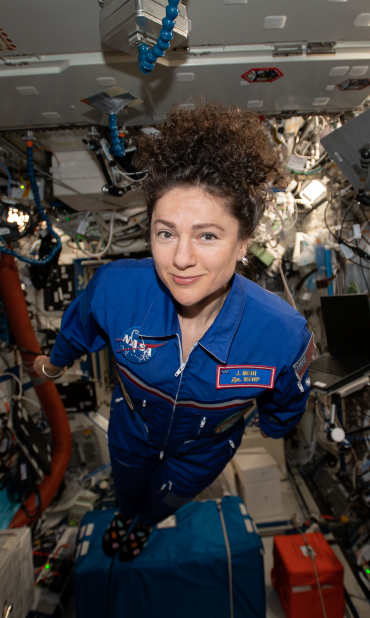

Life on the International Space Station is quite different from life on the ground. Crew members experience multiple sunrises and sunsets each day, spend their time in a confined space, have packed schedules, and deal with microgravity.

These and other conditions during spaceflight can negatively affect the performance and well-being of crew members. Many studies on the space station work to characterize and understand those effects and others try out new technologies and practices to help counter them.

Light Up My Life

A current investigation from ESA (European Space Agency), Circadian Light tests a new lighting system to help astronauts maintain a more normal daily or circadian rhythm. An LED panel automatically and gradually changes the light spectrum and varies from day to day to better mimic natural conditions on Earth. The study seeks insight into this system’s effect on circadian rhythm regulation, sleep, stress, and overall well-being of crew members. The findings also could reveal ways to improve lighting for shift workers and those in extreme or remote environments.

Daily Rhythms

An earlier ESA investigation, Circadian Rhythms, examined how daily rhythms change during long-duration spaceflight and its non-24-hour cycles of light and dark. This understanding could support countermeasures to improve performance and health on future missions.

A well-established way to determine circadian rhythms is by continuously recording core body temperature, but methods to do so can be invasive and inconvenient. For this investigation, researchers developed non-invasive skin sensor technology for measuring body core temperature over extended periods of time.

Astronaut, Phone Home

Missions to the Moon or Mars will experience delays in communications with Earth – as much as 30 minutes each way from Mars. The Comm Delay Assessment investigation looked at how such delays might affect crew members handling medical and other emergencies to help psychologists develop ways to manage the stress of completing these critical tasks without immediate advice from Earth. Results showed that the space station could provide a platform to test communications delay countermeasures. The research also confirmed that communication delays increased individual stress and frustration and reduced task efficiency and teamwork, and suggested that enhanced training, teamwork, and technology could mitigate or prevent these problems.

This is Your Brain in Space

NeuroMapping studied changes to brain structure and function, motor control, and multi-tasking abilities during spaceflight and measured how long it took crew members to recover after a mission. Results published from this work include a study that found no effect on spatial working memory from spaceflight but that did identify significant changes in brain connectivity. Another paper reported substantial increases in brain volume that increased with mission duration and with longer intervals between missions. The researchers suggest that intervals of less than 3 years between missions may not be sufficient for full recovery.

Dear Diary

For the Journals investigation, crew members wrote daily entries that researchers analyzed to identify issues related to well-being. The study provided the first quantitative data for ranking the behavioral issues associated with spending lengthy time in space. Most journal entries dealt with ten categories: work, outside communications, adjustment, group interaction, recreation/leisure, equipment, events, organization/management, sleep, and food. The report provided insight into how these factors affect human performance and included recommendations to help crews prepare for spaceflight and to improve living and working in space.

Don’t Throw Away This Shot

Crew members on the space station take photographs of their home planet for Crew Earth Observations (CEO). These images record how humans and natural events change Earth over time and support a wealth of research on the ground, including studies of urban growth, natural systems such as coral reefs and icebergs, land use, and ocean events. Over time, researchers realized that taking these photographs also improves the mental well-being of crew members. Many of them spend much of their free time shooting from the station’s cupola.

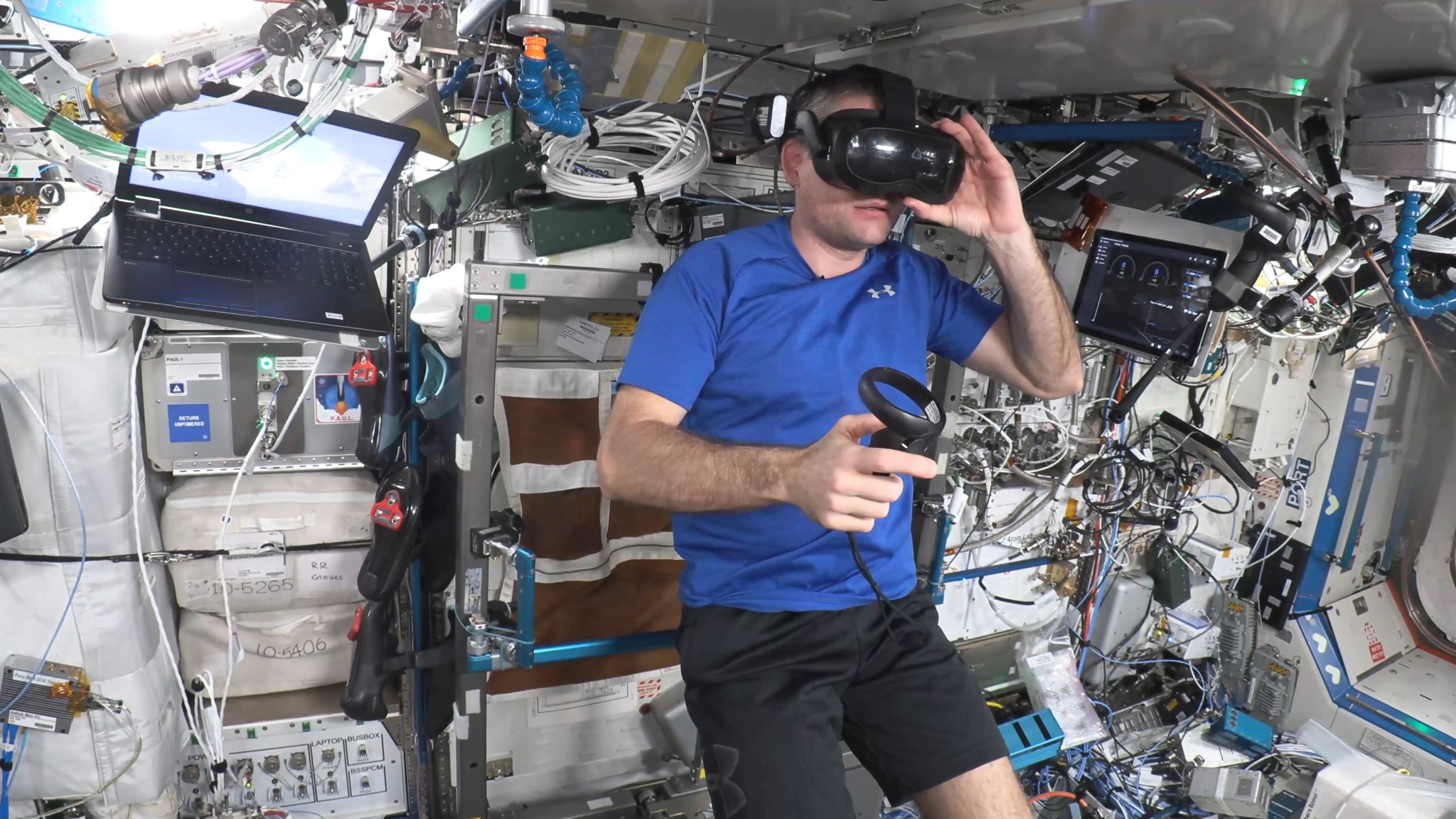

Almost like Being There

ESA’s VR Mental Care tests the use of virtual reality (VR) technology to provide mental relaxation and better general mental health for astronauts during their missions. Participating crew members use a headset to view 360-degree, high-quality video and sound scenarios and fill out questionnaires about the experience. In addition to helping astronauts, this tool could be used to deal with psychological issues such as stress, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder on Earth.

Melissa Gaskill

International Space Station Research Communications Team

Search this database of scientific experiments to learn more about those mentioned in this article.

What's Your Reaction?

.jpg?#)