Interview with Alex Borlaff

OK, we generally start with your early years, your childhood, where you’re from, and a little bit about your family at the time. Where you grew up, I think it was in Spain? Do you have siblings, what did your parents do, that sort of thing. And how early was it in your life that […]

OK, we generally start with your early years, your childhood, where you’re from, and a little bit about your family at the time. Where you grew up, I think it was in Spain? Do you have siblings, what did your parents do, that sort of thing. And how early was it in your life that you developed an interest in astrophysics or the career that you’re pursuing? What got you interested in that?

Well, I was born in Spain. I grew up and lived in Spain until three years ago when I moved here. I studied in a small town in Madrid, very close to Madrid. I grew up in a family with my mom, who was a nurse at an elderly care center, and my father, who was a firefighter. They are both now retired, but before my father was a firefighter. he was a mechanic. In my family there was a very good interest in both medical science and technology to try to understand why things happen. I remember that my father used to, before going to work, set up the TV for me to watch “Beakman’s World”. I think it was a 1980’s or 90’s show about scientists who would explain things to kids. I remember that very vividly. And very early, I started to gain an interest in how things worked and why nature looks like it looks, but I never really had a precise idea of what I wanted to do until very late, say university. When I applied to university, I was hesitating between doing engineering or astrophysics or physics in general, I had no idea. I always wanted to become a pilot, too. I started to think “I want to be an astronaut!” But at some point I said, “OK, this may be very difficult and what happens if you fail? What happens if you never become an astronaut, for example? You must find something that you really like and is worth doing even if you don’t make it.” So I chose physics because it’s a nice way to understand the whole universe, beyond just engineering. But I never lost track of engineering really. I’ve always been in a mixed world.

Do you have siblings?

Yes, yes. My older brother, Saul, is a firefighter too. He chose to follow my father’s trade. He’s very similar to me. I mean, when we are together, we are always trying to repair something, or building an antenna, or going on a hike or something like that. We are very similar.

The last person we talked to, who was also born in Spain and went to school there, told us that in Spain the education is not like here in America, where you can almost go all through college and not actually know what you want to do. But in Spain you must declare earlier, like at the high school level, and pursue engineering or pursue music or science or something, and you get locked in at that point.

Yeah. In Spain we start choosing fields as early as 14 – 16 years old.

I’ve looked at your list of publications and you have an extensive resume of work, so I’m surprised that you only got interested in this recently.

I’ve been very lucky. I have had very bright and supportive supervisors and colleagues all this time who taught and guided me.

Where did you go for your undergraduate and your graduate work?

I did my undergraduate degree and my masters in Madrid. I was still living with my parents there. In Spain we leave the nest pretty late (laughs). I started there in physics in the Complutense University of Madrid, which is the largest public university in Spain, and it was really hard. I had a hard time in the first two years because, to be honest, I’ve never been very good at math.

That would be a problem.

We are doing this in a NASA interview, but I have to say that I had to ask for help from my friends to keep up. In more practical fields, like the subjects that were related to the laboratory or the telescope, I think I was really good. But in the more theoretical subjects I always had trouble. But that was in the first year of university. When we started switching to more astrophysics and more practical things, it went more smoothly.

So, because you were in astrophysics, that was why you decided to continue and pursue a PhD, which is somewhat of a basic requirement in that kind of a field?

Yeah, many of my friends were well focused: you do a degree, then a master’s and a PhD, then you do a post doc, maybe another post doc, and then you are a professor, or something. I never had that path decided. I mean I followed in some way that career, but I think I’ve never been so focused as when I did my master’s and one of my friends said “Hey, are you thinking of doing a PhD in this place? And I was like “OK, maybe that would be interesting, to follow the continual theme.” But I wasn’t sure that I wanted to become a professor. I just thought it would be interesting to do a PhD and then start work at ESA or NASA.

And the place where you got your PhD, the university, was in the Canary Islands, I believe?

Yes, It’s an amazing place, very beautiful.

I don’t know how you could study there. That’s a place people go for vacation!

Oh, yeah! Well, that is true.

A very exotic place, I would think. OK. And then what? Did you get your post doc at Ames because you saw the opportunity posted and applied for it? Or did you know somebody? Was there a connection of some kind that got you to Ames?

Not really, no. But it was a very critical moment in my life because I had just finished the PhD and it was very intense at the end, so I decided to take some months off, and I started working on a personal project which was building a house. It was in Spain, my grandma’s house. It had been abandoned for many years, so my now wife and I decided to repair it and at the same time I was applying to jobs, trying to find a position. It took six or seven months, and I wasn’t really sure exactly where to go. And then I remembered: “OK, first do the harder thing”, so I applied to NASA, ESA, and CNES. I tried to apply to the hardest things that I would probably not get. I just started sending emails to NASA, and one of the people who answered was Pamela Marcum, my supervisor here. She was very nice and we started working on a project together, to submit. And I think it was February 2019, when we submitted. Then I forgot about it and said “OK, they are never going to answer.” And it was probably in June 2019 that she sent me an email, and said: “I probably shouldn’t tell you this, but they are going to offer you a position at NASA”. And I was like, “Wow”!

Wow, indeed!

It was a very scary moment because I had no, absolutely no, experience on how the immigration process for USA and NASA worked, in terms of “When should I be there?” “Can I bring my wife?” “Can she move with me, or do I have to move alone?” But after a couple of days of very scary questions, we were very happy to know we were moving to the United States!

So up until then, you hadn’t really had a reason to master English as a second language?

Well, my PhD and all my publications were in English, so it was necessary for me to learn it, although it is hard to master it from a non-English speaking country.

I saw in one of your bio’s, probably in your resume, where it described your language skills and showed English 100%, Spanish 100%, and even some Russian and some French. I’m always interested in people who are going to somewhere where they don’t speak the language. Or maybe you did at the time, I don’t know, or had but a modicum of English training, especially to an educational setting where it’s important to be able to communicate and understand.

I think that was the moment when I really started to feel more or less comfortable with English. But I must also say that my supervisor was British.

OK, that would help.

He had been living in Spain for 30 years, John Beckman, and he didn’t want to speak in English with Spanish people because to be honest, he speaks Spanish way better than we speak English. He was a lot of help in many ways but not so much for the English. However, moving to the United States teaches you not just the language but the way to express things, the way to make people comfortable with what you say. I think that in this we are way more direct, in some sense, but in another sense, I feel like the Americans don’t want to ‘put flowers’ in questions”, they just want to answer the question, which is something that I really like. So, I was very comfortable very early, although there are many layers of language to be learned.

Wonderful! That’s a great story and pretty direct as far as getting to Ames. Some of the people we interview, their road to Ames is all over the place and just sort of happened, while yours was straight on, right out of your PhD practically, so that’s great.

To be honest, I spent a few months in the European Space Agency as a visitor, but that happened after I applied to NASA, so it was just hanging there.

Good for you! So, you got your PhD, you’ve done your post doc, or at least have been doing it. So now is perhaps a good time to talk about your work, your science, and why it’s important. Because all of NASA’s research and programs are funded by the taxpayers, they have to add value. Can you talk about your work and justify it as to why it should be important to the people who are paying for it?

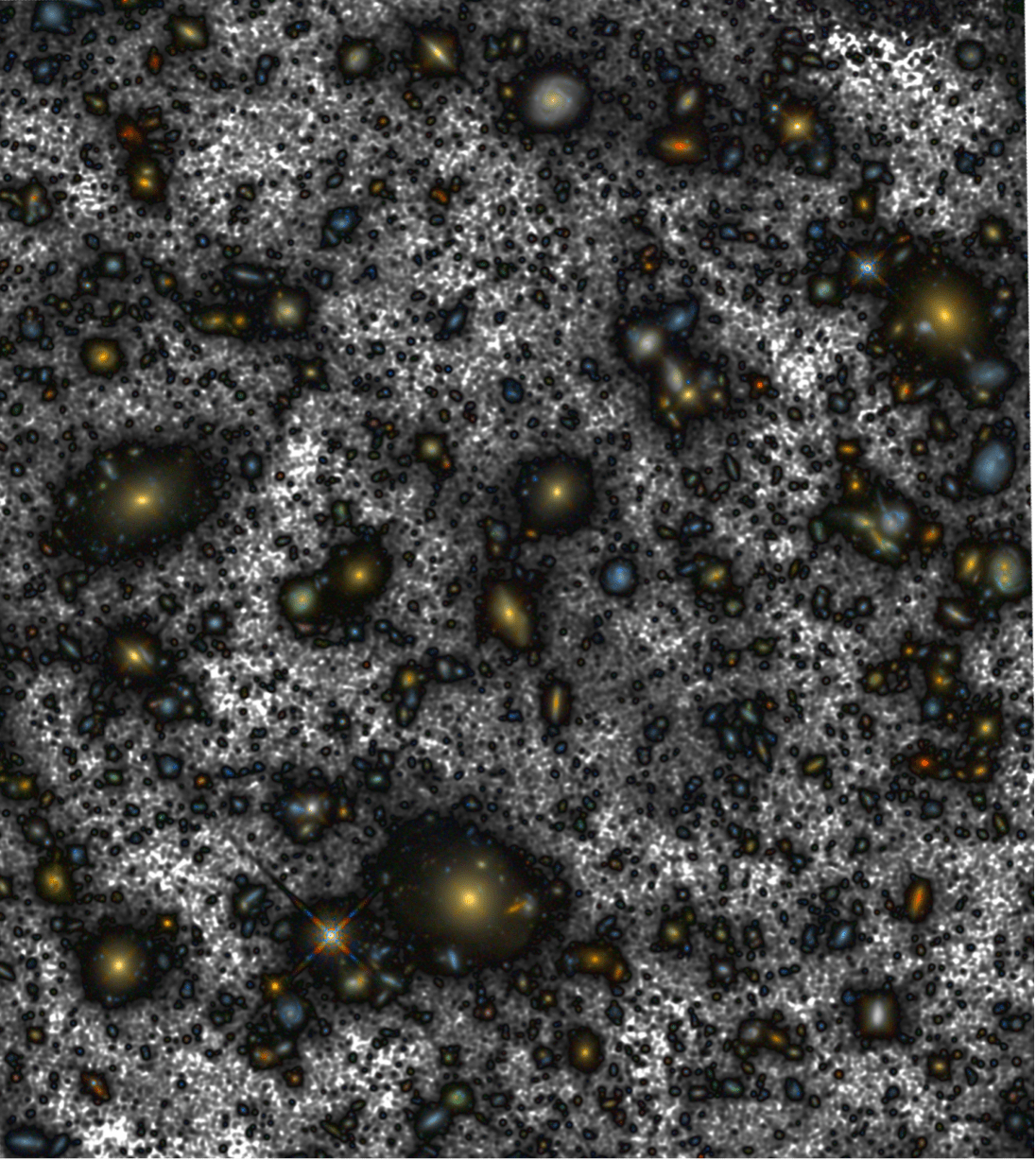

When I started my PhD, we were studying galaxies, basically galaxy evolution. The main idea is that galaxies are the building blocks of the universe. You have planets which are rotating around stars, and stars form groups which are galaxies, but galaxies are the basic unit that builds the universe. You look for something that could make a universe, and it’s a galaxy. It contains all the ingredients to make the universe. And when we look at the picture of a galaxy in space, we always see a bright core and then a disk, maybe with some spiral arms and that’s the end, darkness. It’s just emptiness between galaxies. And this is not really true. Now, we know that galaxies are just like icebergs, in the sense that we only see the tip of them. And when we use more powerful telescopes, they start to grow and grow and grow and become bigger and bigger and bigger, without frontiers. So, space is filled with stars, on and on. That’s it.

The bigger the telescopes, the more you find, that’s absolutely true. And I’m glad you brought up the galaxies because one of the things we will ask you toward the end of this interview is if you have some pictures that represent the things you’ve talked about in your life, your work, or your family, we would like to include those. They’re always very interesting. And I found that picture of the Whirlpool Galaxy.

Oh, yes!

The Whirlpool Galaxy is a classic spiral galaxy. At only 30 million light years distant and fully 60 thousand light years across, M51, also known as NGC 5194, is one of the brightest and most picturesque galaxies on the sky. (nasa.gov/image)

It was labeled picture of the day from some organization, and it was absolutely beautiful. I hope that we can include that picture as part of your post when we get it ready to go.

I think that picture is very beautiful, I would say it has huge emotional value to me because when I landed here at Ames, one of the dream things I wanted to do when I just arrived was to work with the Stratospheric Observatory for Far Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), although I had no relevant experience. We don’t have that kind of facility in Spain. And then I saw a picture of another galaxy called NGC 1068, which is really beautiful.

Magnetic fields in NGC 1068, or M77, are shown as streamlines over a visible light and X-ray composite image of the galaxy. (https://www.nasa.gov/image-article/shaping-spiral-galaxy/)

It was observed by SOFIA. And I sent an e-mail to one of the PI’s of the article, and said: “This is really beautiful. Can I work with you?” (laughs) And just like that he said. “Yeah. I’m in the SOFIA building, just come over and we’ll have a chat”. And two years later I was flying with him in SOFIA!

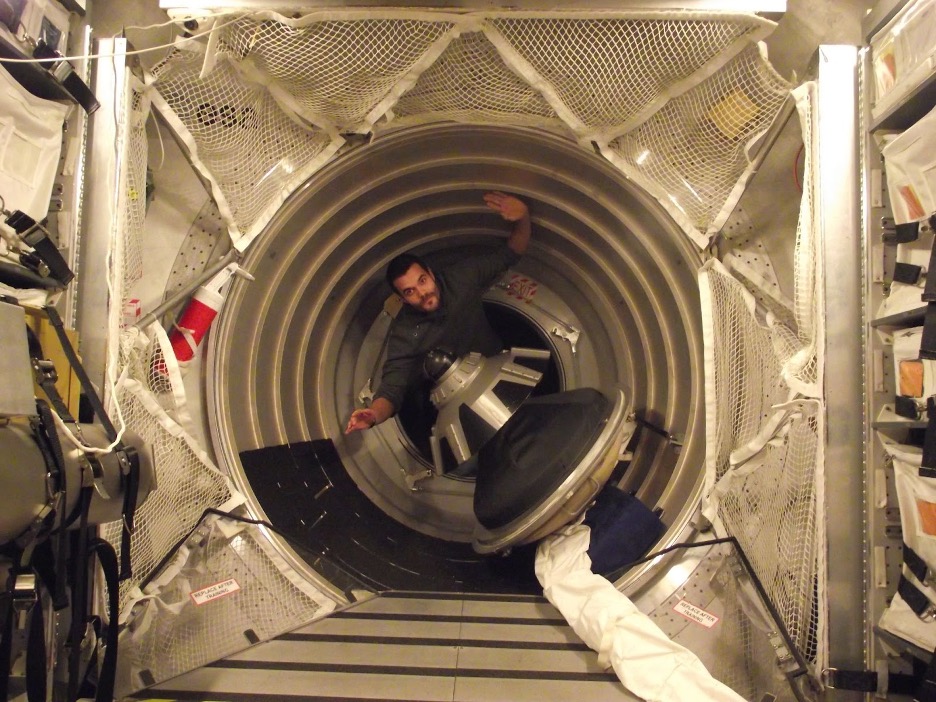

SOFIA, the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, is a Boeing 747SP aircraft modified to carry a 2.7-meter (106-inch) reflecting telescope (with an effective diameter of 2.5 meters or 100 inches). Flying into the stratosphere at 38,000-45,000 feet puts SOFIA above 99 percent of Earth’s infrared-blocking atmosphere, allowing astronomers to study the solar system and beyond in ways that are not possible with ground-based telescopes. SOFIA was made possible through a partnership between NASA and the German Space Agency at DLR.

(Image courtesy nasa.gov)

It was one of the most amazing experiences I’ve ever had. And I know that it would have been impossible if I had never got that position at Ames. So, it’s something that I just can’t explain with words.

That’s a great story and it’s a great picture, one that immediately someone would look at and say “that is beautiful”. And besides being beautiful, what is it? As with science everything we see or discover prompts more questions. So, it’s very interesting. And regarding astronaut training: would you like to talk a little bit about your experience as an astronaut candidate, how that came about, and what it was like?

Sure. I always wanted to be an astronaut and I’m still into it. I remember when I had just started my degree there was the latest call from the European Space Agency for astronauts in 2008. I took notes of everything: how they looked, what expertise they had, and basically with that very limited amount of information you make your way to the next call. So last year they opened this call to the next class of European astronauts in 2022, and I applied. Another friend of mine applied too, and we were like, “OK, we will get ditched in the first cut, so don’t worry about it”. But I got an invitation to the next round. The first round was just sending in the CV and answering a couple questions, very, very general information. But the second round was very interesting: you get a trip to Germany. And there is the psychometrical testing.

Well, you’re a serious candidate when you get to that point.

Yeah, yeah. I mean, when we applied there were 22,000 people in the pool, and in the next round there were like 2,000. I don’t remember exactly the number, 1,000 or 2,000. So we were doing all these psychological tests and screens. We were in a very impressive room, full of other candidates and they looked very, very serious and were answering the questions at the same time, while maybe you were hesitating with some of them. It was very impressive. But something that really got to me is that other candidates were very, very nice. They were all kind. There was no competition at all. People were trying to help each other and keeping calm. They would say “Don’t worry about this. You’ll probably get the next test right”. So then I went home and I said, OK, this time I am absolutely out because I met some people who are absolutely amazing, far better than me. I mean, there were pilots, military, people working in deep cave mines, industry, even Antarctica, who were very, very smart. But I got an invitation to the next step, and these were more personal with rounds of psychological interviews, many, many hours with the psychologists. At this point we were 400 candidates left. I got interviewed by Thomas Pesquet, one of the European astronauts, who asked questions about how you would behave in personal situations, like risk situations, when your life may be threatened and at some point, you start thinking, “I’m just an astronomer. I don’t have many experiences like that.” I mean when I was in Canary Islands, for example, I learned how to dive so I got a few experiences of “your friend is running out of air underwater”, things like that and apparently that got me and other 100 candidates through to the next round, which was very interesting: it was a medical test. Basically, you spend a week in Germany and everything that you can imagine can be tested, will be tested. Everything!

Wow!

But it’s very, very nice because we were not alone, we were eight people from all over the place, living together for a week. We had a Finnish candidate, a German, a British, one of the selected astronauts was with me in that round, and we were getting along all together, it was kind of like “back to school” and we were on a trip. But at that point the selection is completely out of your control because there’s nothing that you can do to fix anything. For example, you may have something in your heart that is perfectly fine to live on Earth, but it’s not OK to fly to high altitudes, and there’s nothing you can do to fix that. At some point you relax, and say, “OK, I’ve done everything I can to be here, to be fit, to be ready”. So, you just had to relax. I was lucky, very lucky, to pass the medical test. I mean, at that point the ones who passed the medical test were like 50 people from the initial 22,000.

That’s amazing!

Yes, it is! And then there was yet another round of interviews (Phase 5) with the head of the astronaut team, and finally the last 25 of us did another interview with the ESA Director General, in Paris (Phase 6), when the last decision was made, so I went through all the process really until the last point.

Sounds like you did, and you could get down to #2, and if they’re only choosing one then you did absolutely everything right, better than everybody else except #1, and at that point it’s somewhat subjective because all of you in the 50 were extremely well qualified.

Absolutely.

And it might have just been the luck of the draw.

I had the opportunity to be there with the best. I think it’s something that makes you feel better because, I have met many of the selected astronauts and they’re all amazing. And when you met someone like that and become friends, you could say “OK, if they had selected me, they would not have selected him or her, and we were just the same.” So that’s how I think of it. I’ll just keep training for the next astronaut selection.

You probably made a lot of friends. Talk about networking! My goodness, you’ve got a network of people from around the world that you’ve gotten to learn and to know and be close to and are probably lifelong friends with some of them. So that is great. Well, I admire your ambition to do this and the effort and determination that you showed to go all the way to the end of the sequence, and it takes away nothing from you that they wind up selecting someone else. So, are you going to age out of this or are you going to take another shot at it?

Well, it takes some time to rebuild everything but at some point, you realize, “Hey, I am 32 years old. I’m working at NASA, I made it to the last round of an astronaut selection, so I’m physically fit, I passed the psychological test, so I think I have more reasons than ever to apply again. So if another opportunity appears, sure I will apply.

Well, you’re already an impressive success in your pursuits, in your career and in your work, so congratulations on that. You mentioned your wife. Would you like to say anything about your family? I don’t know if you have children, or you have pets or . . .?

No, we don’t have kids yet! We live here in Mountain View and well, I think this story is also her story because when we moved together to the United States, she was finishing her master’s degree in psychology, and after that we would both be unemployed. So, when we moved here together, we were like, “OK, this is a huge opportunity, but we’re going to be starting from zero.” Find a job, find out how to get our transcripts from the university to the United States and everything.” She also had a really hard time to figure out the way through the American system of education. But she made it and she’s now working at Stanford Pediatrics. She’s studying brain development of preterm babies as a research coordinator.

Stanford Pediatrics, wow! That’s impressive. I would think there would be quite a competition for those jobs.

Yeah, it was a very long interview process for her.

Well, good for her.

She’s got some very good skills. She worked as a therapist with kids with autism, and she is an experienced researcher in psychology. So, at some point this group at Stanford was looking for someone who was able to work with kids and with magnetic resonance, to understand how the brain works and how it develops over time. So, she was the perfect fit. She is very happy and loves her work.

During this pandemic, you came to Ames in 2019, and you live in Mountain View, so the closing of the Center probably didn’t affect your commute? Are you able to do your job pretty much remotely? You don’t have a lab or anything that you have to come in for?

Well, most of my job, I can do remotely. I think that the impact was from a more personal point of view because when Covid hit we had been in the USA for only five months. We barely knew anyone. So, it was a more personal impact in the sense that we had just moved here and part of constructing a routine is to go to work, meet some people, friends, maybe establish a network and meet some coworkers to have coffee with. But with the pandemic everything became surreal because we were just working through our computers and at some point, it’s hard to believe that you’re working where you are working and that there are many, many people on the other side of the screen. It takes some real effort to keep your mind healthy in that environment because it’s very easy – not just for us here at NASA but for everyone, students or everyone that was working and starting a career – to be distracted and become affected by imposter syndrome. When you are working in long isolation through a computer it is not hard to start losing track about who cares about what you are doing and who is interested in it because you are just sending emails, submitting papers, and proposals. So, I think it’s very important to keep track of and keep in contact with students and people working remotely. I think without a physical place to work, you enter this university with people and a big logo in the door and I think that’s something important because you get inside and It’s like, “OK, I’m part of this community, part of this university, part of NASA, part of Stanford, part of whatever you’re working with.” You can miss some of that if you’re just working remotely, you miss a lot of that. I think it takes a lot of effort to continue working in that kind of condition but obviously we’re in an emergency and there are some priorities, but it’s not easy.

You mentioned impostor syndrome. Refresh my memory of what that is and how it affects your sense of communicating with your colleagues.

Well, imposter syndrome is a psychological condition that makes you doubt your skills or accomplishments. It happens a lot when you are working on something very specific, for example in science it is super common, you get the idea that what you’re doing is not important at all and it may not be affecting other people. I would say that 90% of the astronomers I know have been affected by this at some point, and think “OK, this is not important, what I’m doing. How do I transform this knowledge that I am working for to a real impact on the community?” That’s something that I think becomes way more common and harder when you are isolated in your house.

So, it makes you feel less important or less valued, as if you were an imposter and everybody else is real but you’re not?

Yes, exactly that. I think in astronomy it is particularly easy to get that because everything is so far away. It’s hard to keep track of what is the real impact of what you’re doing right here and now. For example, that was one of the questions in the astronaut selection process. One of the questions was “OK, you are an astronomer. Why do you think that is important? Why should we care?” My answer is I’ve been working my whole life with the Hubble Space Telescope, so I said, “Well, the Space Telescope discovered that 95% of the universe is not made of the same atoms that are here in this room. It’s like someone told you that magic exists.” And I think that’s amazing. It was a pretty honest answer. I was saying “That’s important. It may be far away, but it’s important.”

So, you’re doing well in your career and ambitions and so forth. What advice would you give to a student just starting out who would like to have a career like you’re having?

Well, it’s hard to give just one piece of advice, but I would say to find something that you really like and work on that. It may be hard, you may want to become a scientist, or a doctor or anything else, and it may be really hard, but I think it’s harder to work on something that you don’t like for your whole life.

That’s a good point.

I think it’s way, way harder, but at the same time it’s hard to land exactly where you want. In my experience, there is no plan that survives the implementation. You make a plan and think that you’re going to do something, but it never happens the way that you think it will. My strategy was to, in a more practical way, find many things that I really like and apply to all of them, starting from the hardest to the to the easiest one. Well, I succeeded in having a post doc at NASA, but before that I applied to 20 jobs, and I never got any. It was just really rejection, after rejection after rejection. So, I consider my myself very fortunate to be here, but I cannot say that it was the first shot. I think that in the time of social media it’s very easy to just see the stars, the successes of people. No one publishes “Oh, I got rejected at NASA”. But that happens obviously.

That’s good. I probably misstated it when I said that your path has been fairly direct, but you had a lot of rejections along the way and you have to not let them beat you down, but just keep going with what you’re passionate about.

Yeah, and that applies also to the astronaut process. I mean you may want to be an astronaut, then you apply, but it is true that, for example, the commander of Apollo 13, James Lovell, applied to be one of the first round of Mercury astronauts but he got cut for medical reasons and yet he applied again, and he became an astronaut. There are many examples of great people that had to apply many times.

So, we’ve talked a lot about your work. It’s fascinating, but we also want to touch on a few other things, and one of my favorite questions is: you’ve got all this stuff going on in your life with your work and all that, but what do you do for fun?

Well, I grew up in a house full of tools and I like doing things with my hands. We have a pretty old car here, a Subaru from, I think it’s 22 years old now! And I really like to spend time with it learning mechanics. It’s something that I really enjoy. And moving here to the United States was also a blessing for doing hiking and camping around. I’m still trying to comprehend the beauty of the American wilderness. California is amazing. I mean, we are planning a road trip around the United States and traveling is something that I really, really love. It’s something that I could do partly because of my job, but also just for fun. It’s just something that I really, really enjoy.

Do you have any musical talents, perhaps? Play any instruments?

I’ve never been a good musician. I like music, I like music a lot. I listen to it. I enjoy many types of music, mostly rock, electronic, but many other types of music, but I’ve never been gifted with the talent of playing an instrument with my hands.

Well, I regret that I haven’t either, but that’s the way my life has worked out. How about your taste in reading? What book might we find on your nightstand?

Well, right now I’m a lot into psychology books and essays. My wife has started sending me books to better understand her job. And there’s this book called “A Primate’s Memoir” by a professor at Stanford named Robert Sapolsky. It’s a really good book. I read it very recently. It’s an amazing story about this scientist who went to Kenya to study baboons at the age of 19 or 20, with barely any money, doing a PhD in baboon psychology and it’s just amazing. I mean, I love that book.

We also like to ask who, or perhaps what, inspires you?

Wow. Ah, well, that’s a hard question. I don’t know if it’s a single person, but well, of course there’s my PhD supervisor, John Beckman. He has been a huge inspiration to me. He’s an astronomer working at the Canary Islands, but he was also working at NASA Ames thirty years before me, working with this mission called “ASSESS”. They were flying on an airplane to train astronauts, European astronauts, before the first selection of astronauts happened, in the ‘80s. They were working with astronaut Claude Nicollier who would fly twice to repair the Hubble Space Telescope in orbit and basically, they were training human beings to become mechanics in space, which is really hard. And after that he was working also on airborne astronomy with the Kuiper Airborne Observatory and a Concorde that was meant to observe the solar eclipse. He has done many, many things throughout his life, which to me is an inspiration because it is a demonstration that you can have many lives.

We’ve already talked about images and pictures. And we’re going to ask if you will include some pictures when you return the transcript with whatever corrections and changes you make. We do have another question: Do you have a favorite quote or saying, something that you think about or that guides your life values or philosophies?

Well, I think we may be very typical, but one thing that I think of every time we try to do something: “We do it because it is hard”. That’s from John Kennedy and I think it is very inspirational.

Yes, that’s a good one.

Because that includes many things that we do here. Sometimes, for example, when we do astronomy, we always try to justify things because there are useful, like we are going to extract energy from dark matter, but that’s not true. I mean that’s not why we do things. Sometimes it is just because it’s hard. Like why do you want to repair the Hubble Space Telescope? Because it is hard. Because you want to do something that’s really difficult and it will prepare you for the next thing, and so on. So, I will just stand with that quote.

I like that. That’s inspiring. And I did see one item that I kind of skipped past and that is: if you weren’t an astrophysicist for NASA, what would your dream job be?

I don’t know. I think I would say that my other chosen degree would have been engineering, but that’s very similar to what I do now. I think I could easily become a mechanic or a firefighter, like my dad. (laughs).

I was wondering if you were going to go back to firefighter!

Yeah, I mean, it’s not just my father and brother. It’s my cousins and half of my family are firefighters. So, I’m kind of the black sheep! (laughs)

And you said your parents are retired?

Yes, they are both retired. They are happily retired. Right now, they are starting to enjoy their retirement. They are traveling.

Well, knowing how young you are, that makes me feel old! That your parents are retired. Is there anything that we didn’t ask that you wish we had asked, as part of this interview?

No, I think I think everything was covered. It was very complete. Just to say thanks to you all and to NASA for everything.

OK. Well, thank you. This has been a delight and we’re very glad that you carved out some time to do this. I think it’ll turn out to be wonderful. It usually takes me a couple of weeks to get this on paper and get it back to you, and then you can go through it and then we’ll put it in the queue and then you’ll get your 15 minutes of fame up on our website! And after that it goes into the archive and it’s there forever. And that website is open to the public, so your friends, family, and other people can read your interview.

That’s perfect. My mom is going to love it!

Oh, I’m sure. Wonderful Alex. Thank you so much again for chatting with us this morning and we’ll get busy on it and get back to you when it’s ready for your review.

Thank you so much.

Interview conducted by Fred Van Wert and Mark Vorobetz

What's Your Reaction?

.jpg?#)