Eclipses Near and Far

On April 8, 2024, North America will witness its last total solar eclipse for more than twenty years. Other parts of the world will experience the rare celestial event in the coming decade. A total solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes directly between the Sun and the Earth, blocking its disk from view but […]

On April 8, 2024, North America will witness its last total solar eclipse for more than twenty years. Other parts of the world will experience the rare celestial event in the coming decade. A total solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes directly between the Sun and the Earth, blocking its disk from view but making its corona visible in a dazzling display. Although spectacular when seen from the ground, observed from space, solar eclipses appear as large shadows moving across the face of the Earth. The unique geometry of the Earth-Sun-Moon system allows total solar eclipses to occur. Eclipses also occur outside the Earth-Moon system, although the geometries of those worlds rarely if ever produce the stunning display visible on Earth. Spacecraft exploring other worlds have documented these extraterrestrial eclipses.

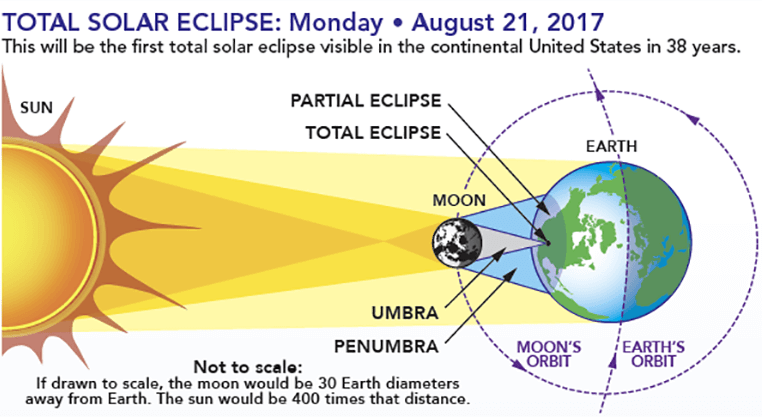

Left: Schematic geometry of a solar eclipse; sizes and distances not to scale. Right: Path of the April 8, 2024, total solar eclipse. Image credit: courtesy Sky & Telescope.

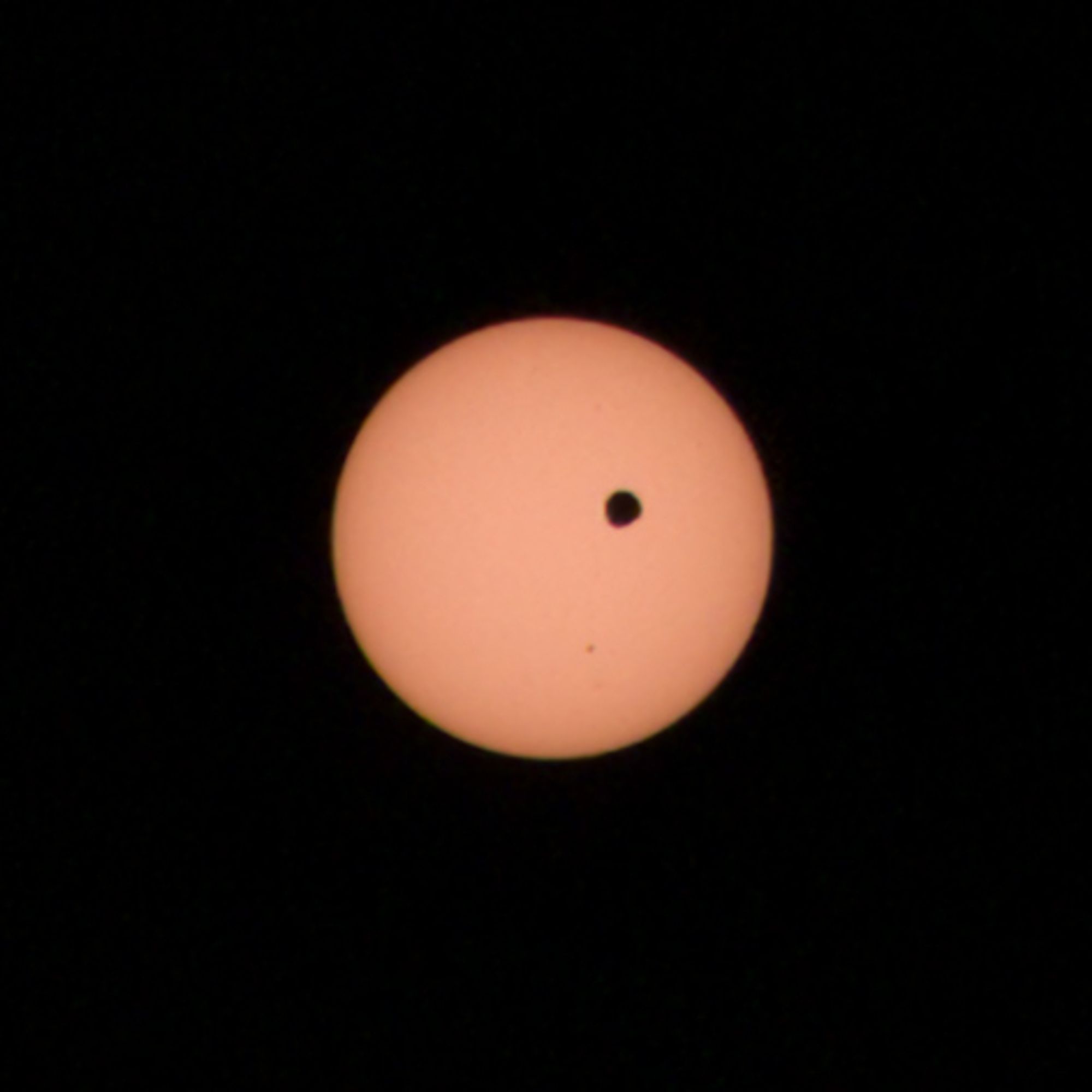

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between the Sun and the Earth, with the Moon casting its shadow on its home planet. Although the Sun is much larger than the Moon, it is also much farther away. As seen from Earth, the Sun and Moon have roughly the same angular diameter and appear roughly the same size in the sky. A total eclipse occurs when the Moon blocks out the Sun’s disk entirely. Because the Moon does not orbit in a perfect circle around the Earth, it appears smaller at its farthest point thus creating annular eclipses. Moons around other planets can also create eclipses although their different sizes relative to the Sun do not create our familiar eclipses. Planets with multiple moons can have more than one eclipse occur at the same time.

Left: Gemini XII astronauts photograph the total solar eclipse from Earth orbit in November 1966. Middle: Surveyor 3 observes a solar eclipse from the Moon in April 1967. Right: In November 1969, Apollo 12 astronauts returning from Moon experienced a solar eclipse as the Earth blocked the Sun shortly before splashdown.

Gemini XII astronauts James A. Lovell and Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin for the first time photographed a solar eclipse from Earth orbit on Nov. 12, 1966. Sixteen hours into their flight, the nearly total eclipse came into view as they flew over the Galapagos Islands and Aldrin took several photographs and a short film clip. Calculations showed that Gemini XII passed within 3.4 miles of the center of the eclipse’s path that traversed South America. The Surveyor 3 spacecraft observed the first solar eclipse from the Moon on April 24, 1967. Unlike solar eclipses observed on Earth, this time the Earth itself blocked the Sun – observers on Earth saw the event as a lunar eclipse as the Moon passed through the Earth’s shadow. In November 1969, as Apollo 12 astronauts Charles “Pete” Conrad, Richard F. Gordon, and Alan L. Bean neared Earth on their return from the second lunar landing – during which they visited Surveyor 3 – orbital mechanics had a show in store for them. Their trajectory passed through Earth’s shadow, treating them to a total solar eclipse. From their perspective, the Earth appeared about 15 times larger than the Sun. Gordon radioed Mission Control, “We’re getting a spectacular view at eclipse,” and Bean proclaimed it a “fantastic sight.” Conrad reported on the rapidly changing scenery, with the Sun illuminating the Earth’s atmosphere in a 360-degree ring with ever-changing colors while the planet remained pitch black. In the darkness, they could see flashes of lightning in thunderstorms appearing as fireflies. As their eyes adapted to the dark portion of the Earth, they saw landmasses such as India and even city lights. In the center of the Earth’s dark disc they reported seeing a large bright circle that turned out to be the glint of the full Moon reflecting off the Indian Ocean.

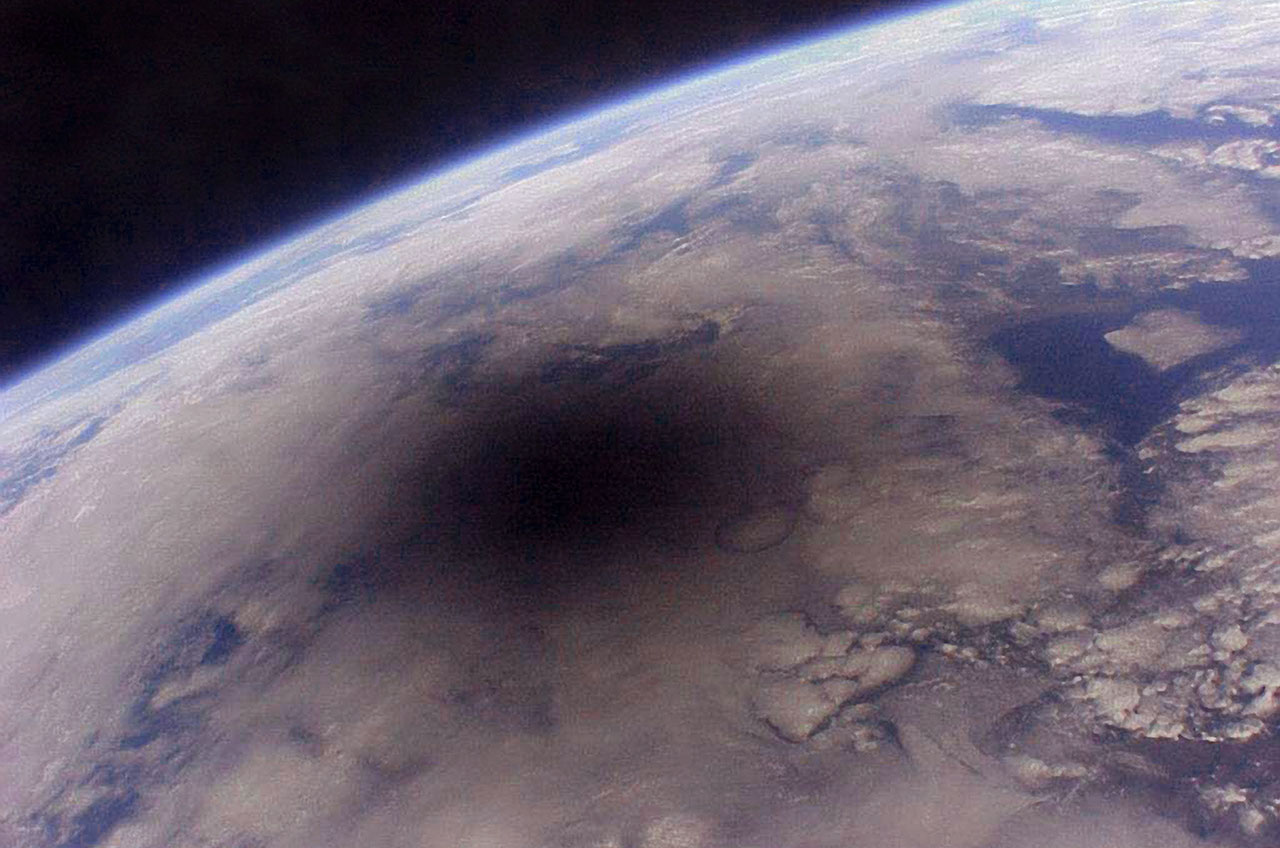

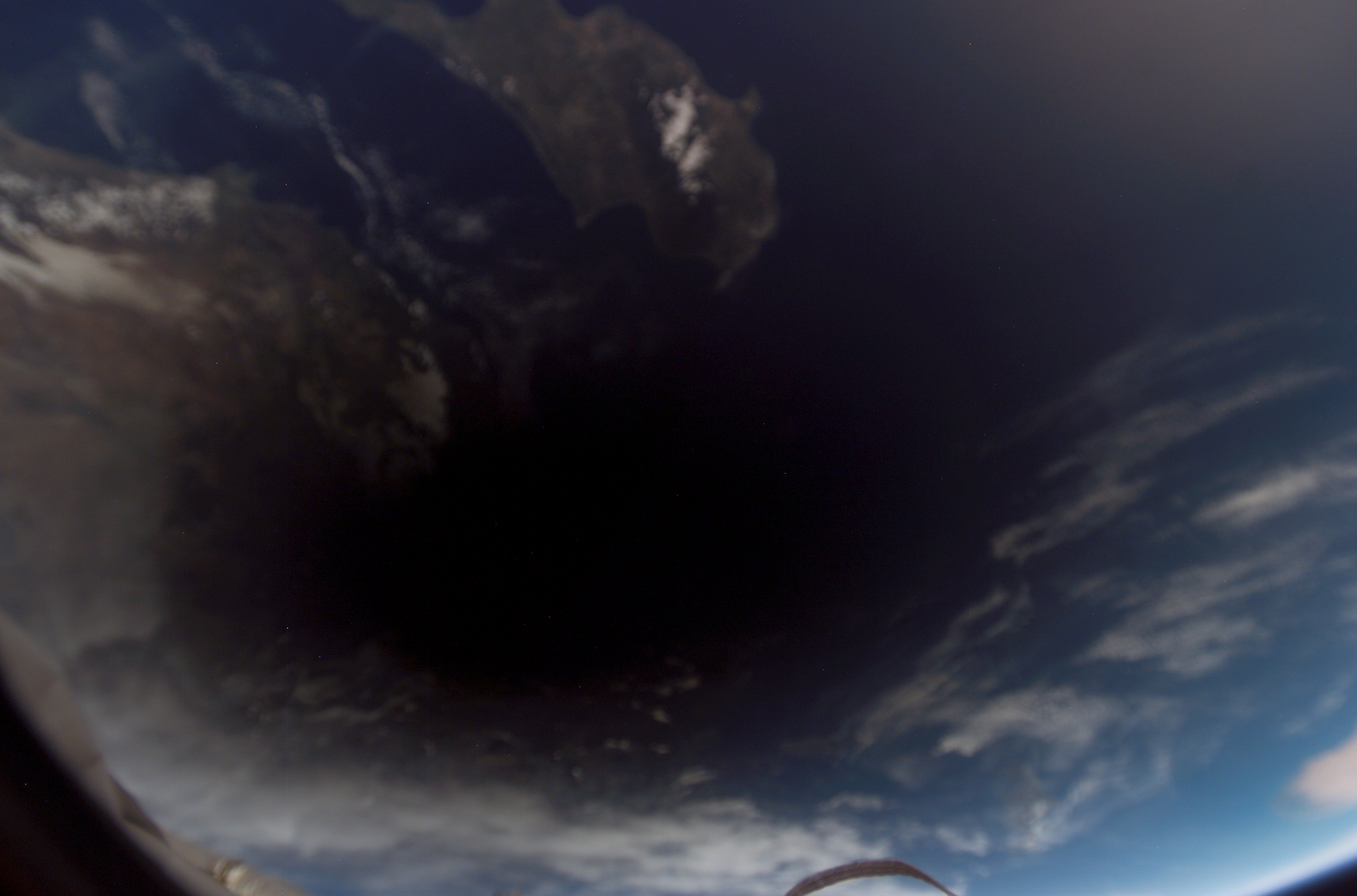

Left: The Moon’s shadow photographed from Mir during the August 1999 eclipse. Image credit: courtesy French space agency CNES. Middle: NASA astronaut Donald R. Pettit observed the first solar eclipse from the International Space Station during Expedition 6 in December 2002. Right: Pettit’s second eclipse during Expedition 31 in May 2012.

The credit belongs to French astronaut Jean-Pierre Haigneré for taking the first photograph from Earth orbit of the Moon’s shadow during a solar eclipse. He photographed the Aug. 11, 1999, total eclipse pass over England while onboard the Russian space station Mir as an Expedition 27 flight engineer. NASA astronaut Donald R. Pettit claims the title as the first person to photograph an eclipse from the International Space Station when he observed the Dec. 2, 2002, total eclipse during Expedition 6. As an additional claim, on May 20, 2012, Pettit observed his second eclipse from the space station during Expedition 31, this one an annular eclipse over the Western Pacific Ocean.

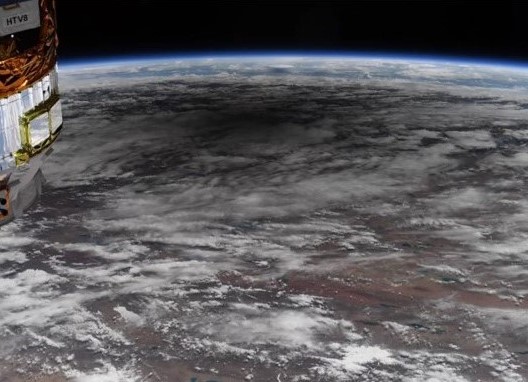

Left: Expedition 12 image of the March 2006 total eclipse over the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Middle: Expedition 52 image of the August 2017 total eclipse over North America. Right: Expedition 63 image of the June 2020 annular eclipse.

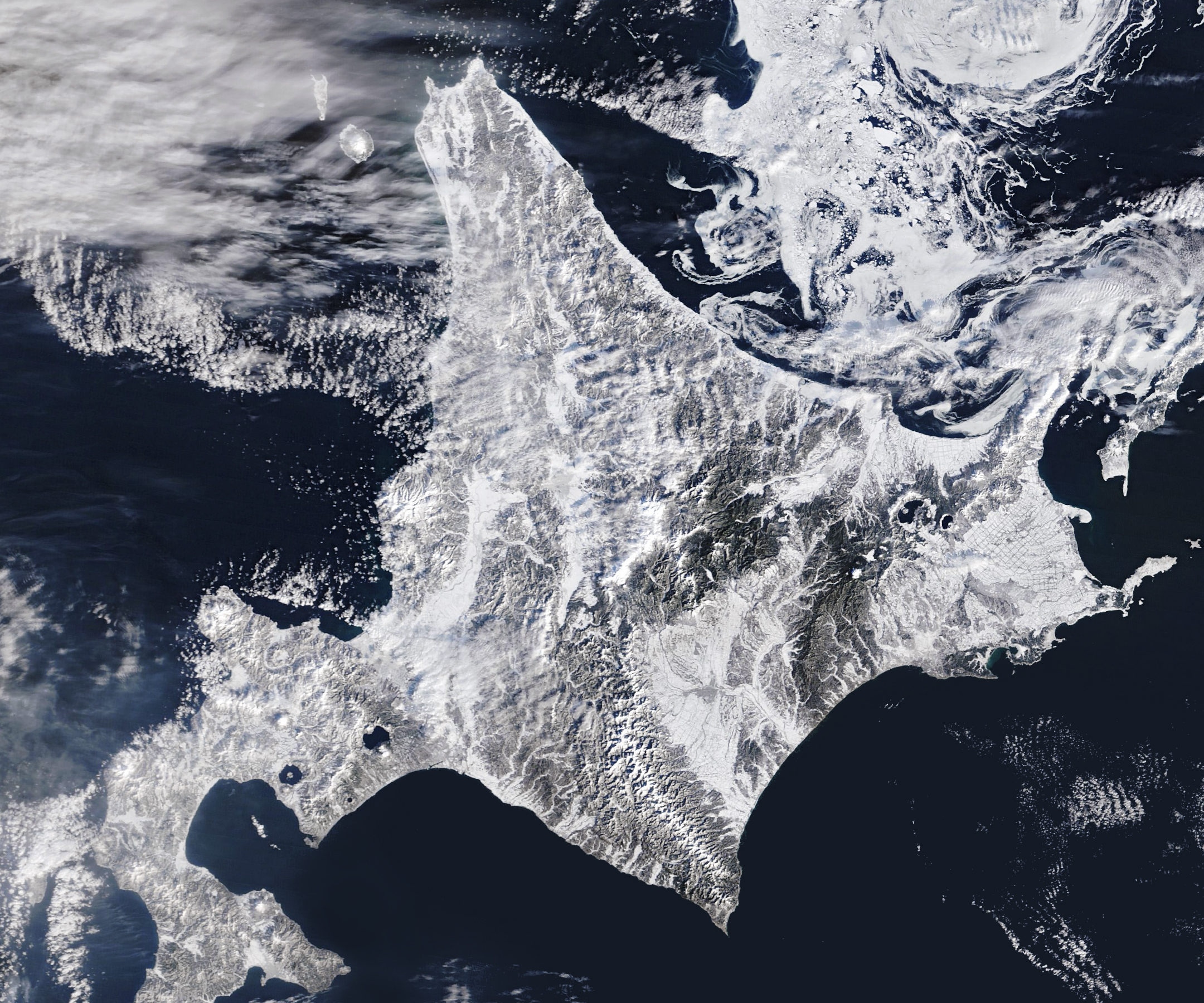

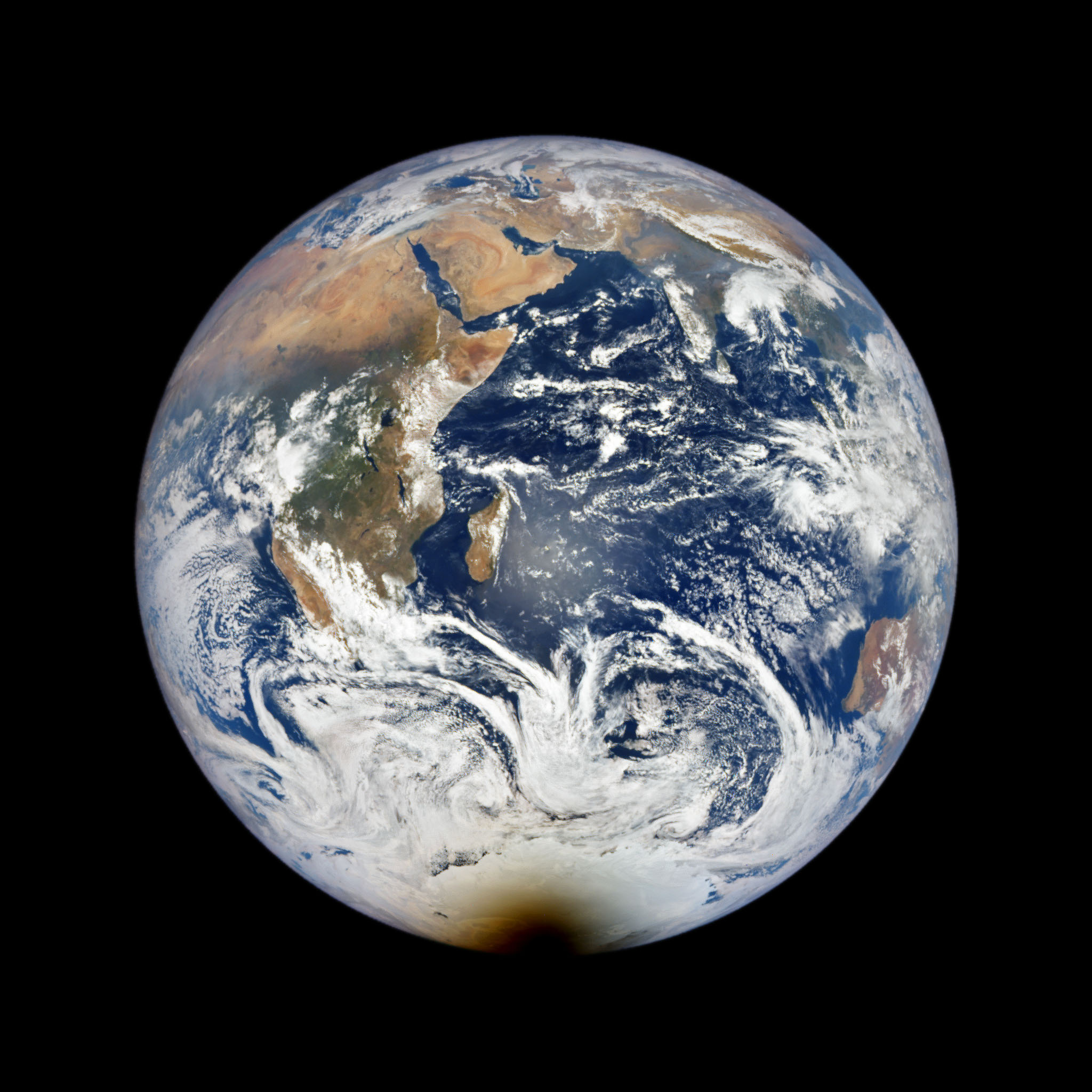

Left and middle: Two views of the eclipse over Antarctica in December 2021, from the Expedition 66 crew aboard the space station, left, and from the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) satellite. Right: DSCOVR image of the October 2023 annular solar eclipse over North America.

Space station crews have observed and documented a number of solar eclipses in addition to Pettit’s two sightings, their ability to see the Moon’s shadow as it traverses the Earth’s surface determined by their orbital trajectory. Expedition 12 observed the total eclipse on March 29, 2006, Expedition 43 documented the total eclipse on March 25, 2015, Expedition 52 observed the most recent total eclipse visible from North America on Aug. 21, 2017, Expedition 61 observed the annular eclipse on Dec. 26, 2019, Expedition 63 saw the annular eclipse on June 21, 2020, Expedition 66 imaged the total eclipse over Antarctica on Dec. 4, 2021, and Expedition 70 viewed the annular eclipse visible in North America on Oct. 14, 2023. Positioned nearly one million miles away at the L1 Earth-Sun Lagrange point, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) satellite keeps a watchful eye on Earth’s climate. NASA’s Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC), a camera and telescope aboard DSCOVR, has taken stunning images of the Moon’s shadow during eclipses as well as the Moon transiting across the face of the Earth.

Mars

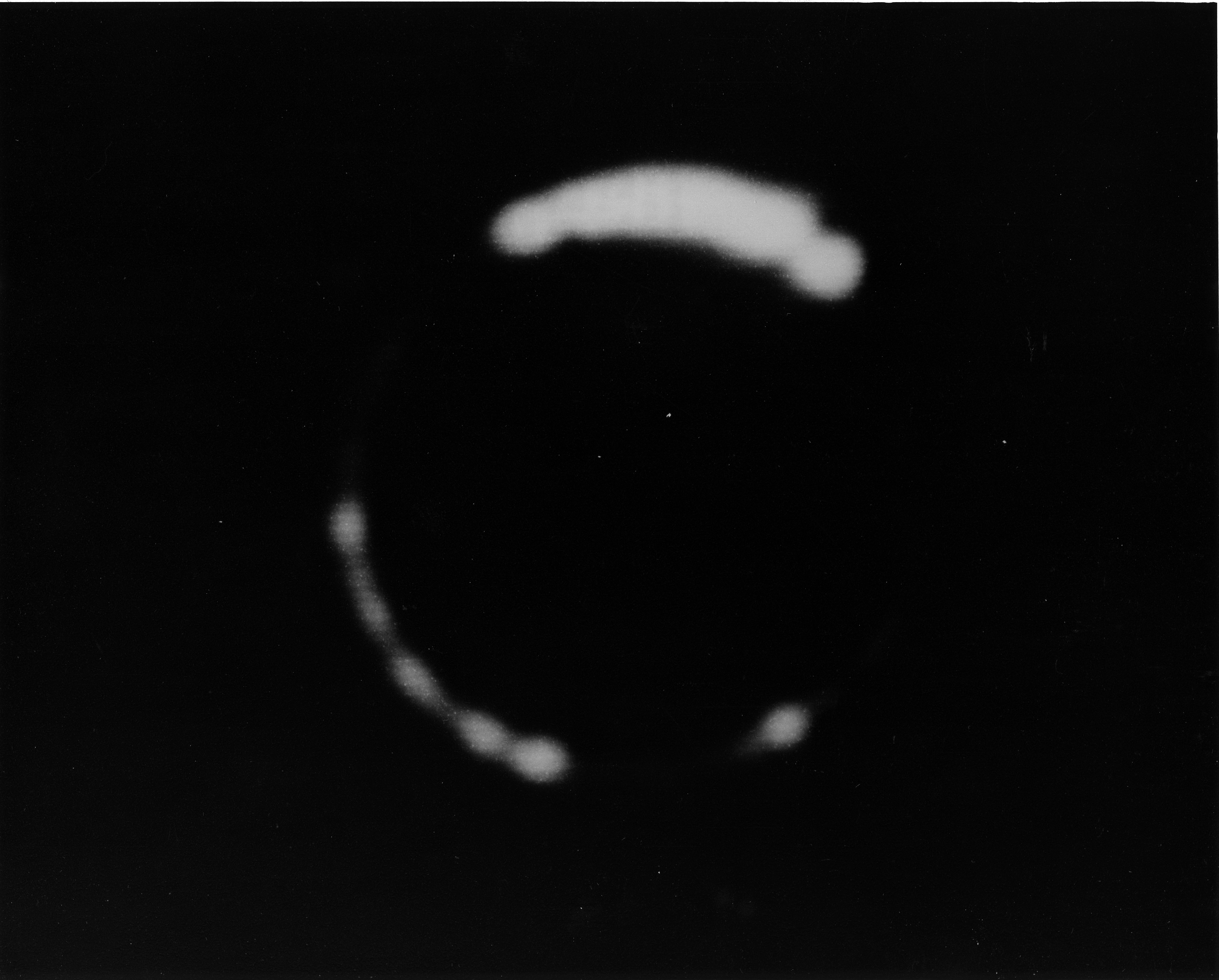

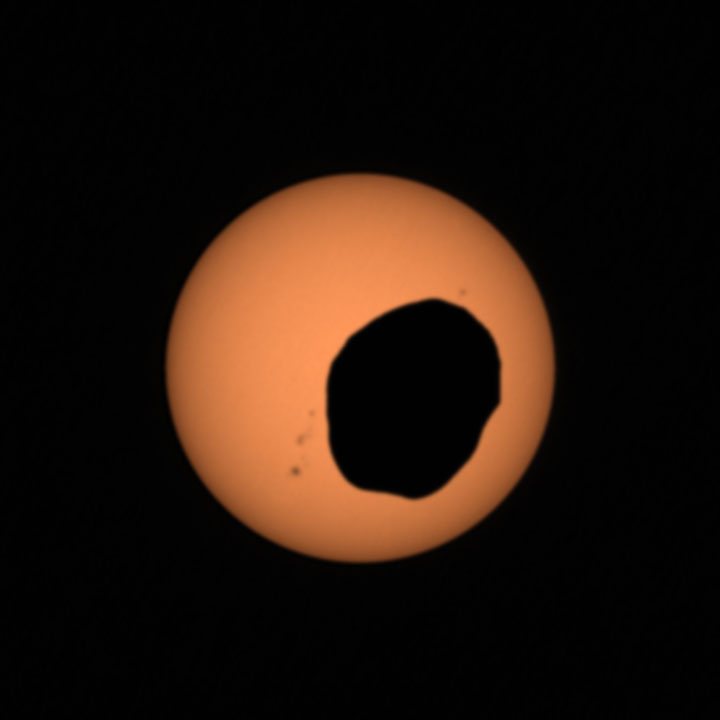

Beyond the Earth-Moon system, eclipses do not occur on Mercury and Venus since they lack natural satellites to block out the Sun. Mars has two small satellites, Phobos and Deimos, both too small to fully eclipse the Sun, even though it appears only half as big as on Earth. Several rovers have captured Phobos and Deimos as they form annular eclipses. Some astronomers contend that due to the small sizes of the Martian satellites, especially Deimos, compared to the Sun, these are technically transits, not eclipses, but no formal definition exists. The Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity imaged the first eclipses from the surface of Mars shortly after its arrival on the planet, first of Deimos on March 4, 2004, followed by Phobos three days later. More recently, the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover imaged the annular eclipse of Phobos on April 20, 2022, and the eclipse (or transit) of Deimos on Jan. 22, 2024.

Left: Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity images of Deimos, left, and Phobos crossing in front of the Sun. Middle: Perseverance image of a Phobos annular eclipse in April 2022. Right: Perseverance image of a Deimos eclipse (or transit) in January 2024.

Jupiter

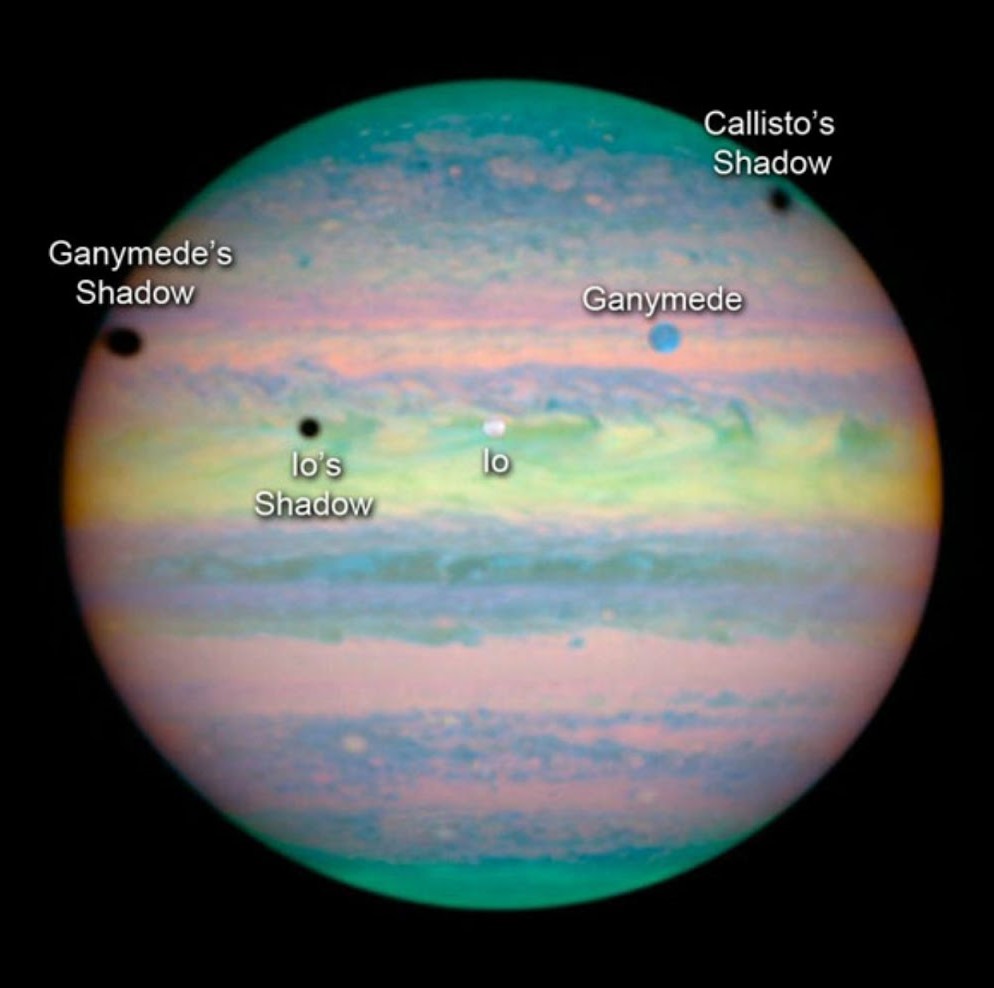

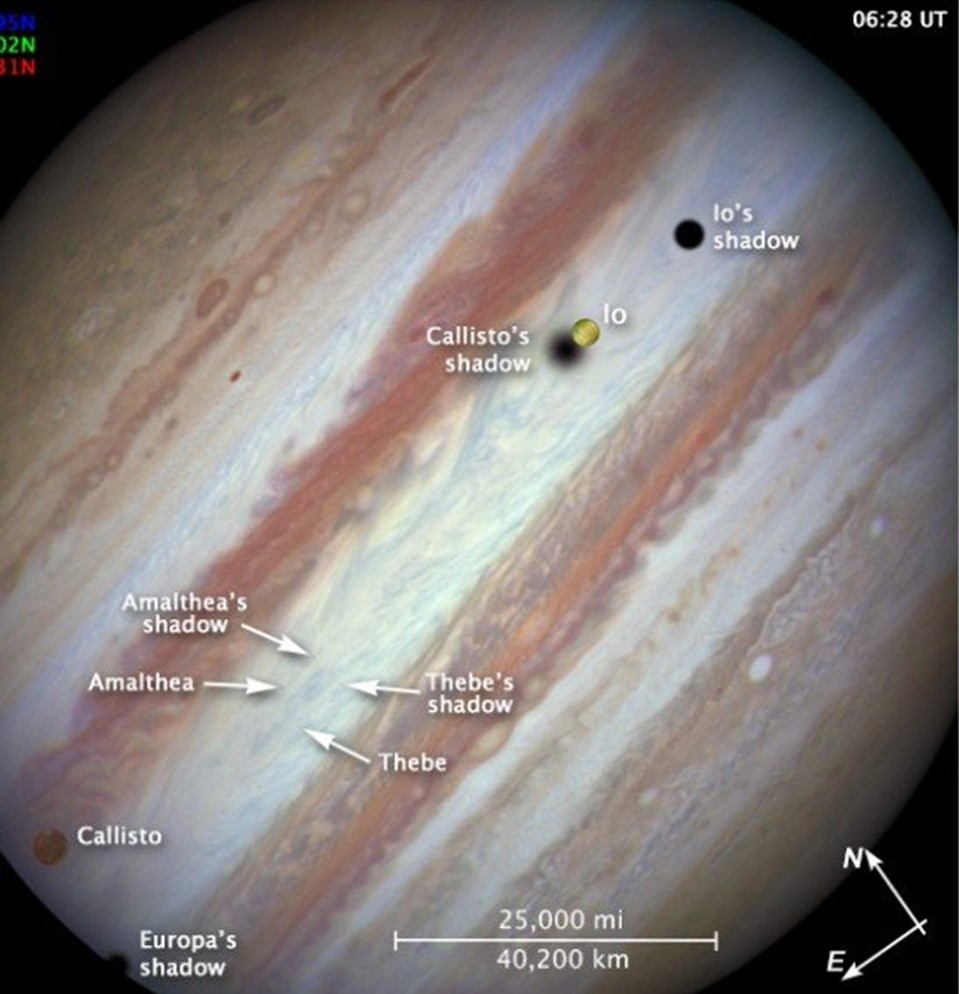

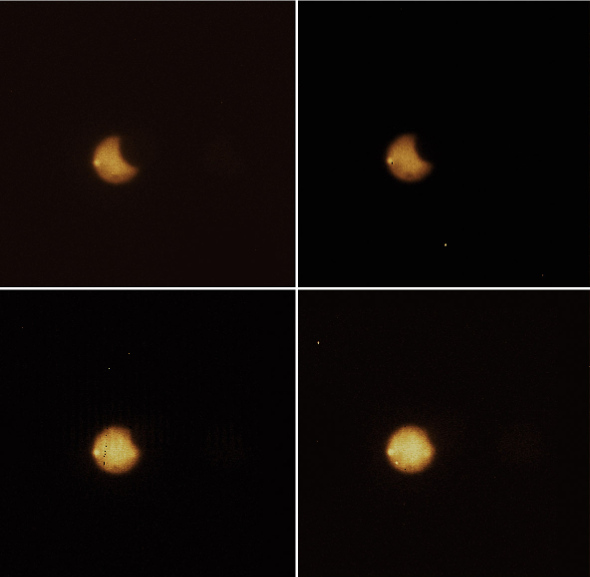

Left: Hubble Space Telescope infrared image of a triple eclipse on Jupiter on March 28, 2004, with moons Ganymede, Io, and Callisto casting shadows on the planet. Middle: Hubble Space Telescope image of the Jan. 24, 2015, multiple eclipse on Jupiter, with five of its moons – Callisto, Io, Europa, Amalthea, and Thebe – casting shadows on the planet. Right: Europa eclipses Io in December 2014, as observed through an Earth-based telescope. Image credit: courtesy Jen Miller and Joy Chavez, Gemini Observatory.

Since the outer gas giant planets do not have solid surfaces, no spacecraft has imaged an actual eclipse by one of the multitude of moons orbiting these worlds. What we can observe, through ground-based and orbiting telescopes and spacecraft are the shadows cast by the moons on their home planets. Eclipses on Jupiter are not exceptionally rare given the planet’s large size compared to its many moons and greater distance from the Sun. Only five of Jupiter’s moons, Amalthea, Io, Europe, Ganymede, and Callisto are either large enough or close enough to the planet to completely occult the Sun. And given the low tilts of the moons’ orbits, they cast a shadow on every revolution. Double, triple and multiple simultaneous eclipses are not uncommon. The Hubble Space Telescope has observed numerous such events. Given the number of Jupiter’s moons, especially the four large Galilean moons, and that their orbits all lie very close to Jupiter’s equatorial plane, they occasionally eclipse each other, with the outer moons passing between the Sun and the inner moons. When Earth passes through Jupiter’s equatorial plane, fortunate observers can capture these rare events using ground-based telescopes, sometimes accidentally as they observe the Galilean moons for other reasons.

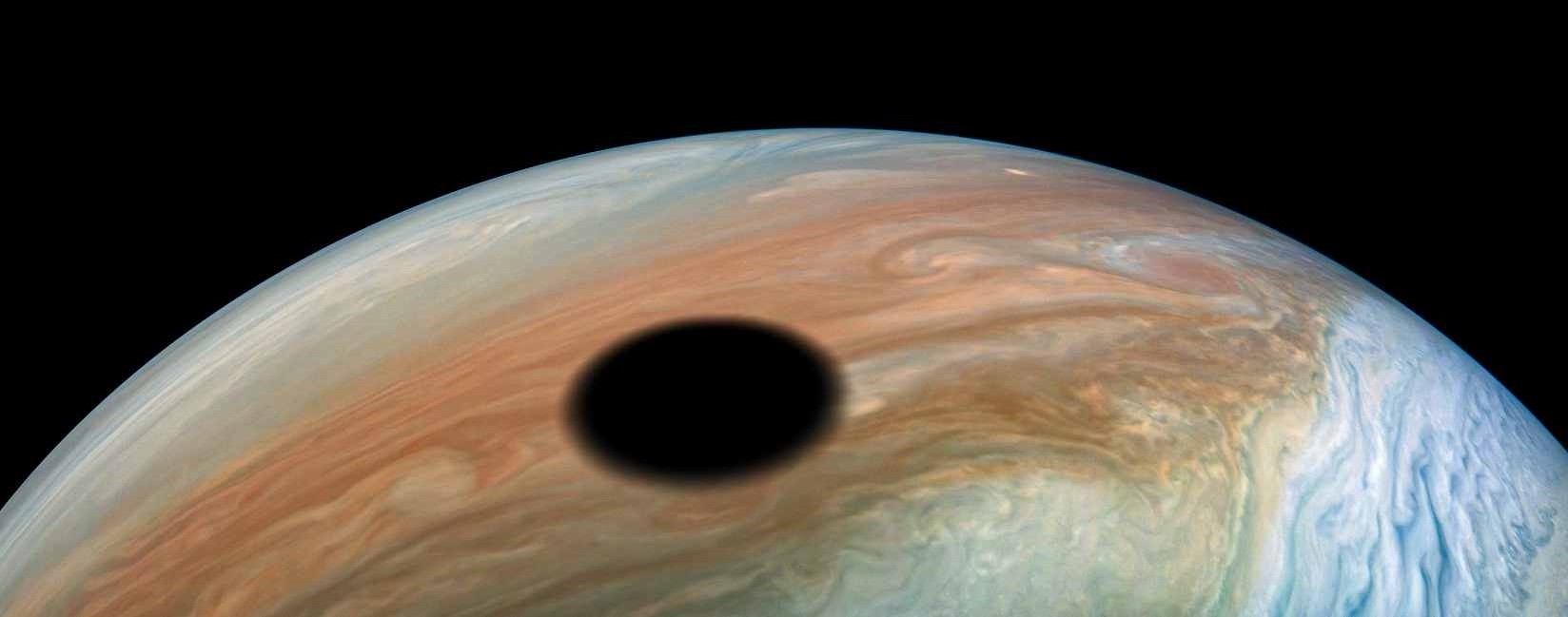

Left: Juno image of Io’s shadow on Jupiter in September 2019. Right: Juno image of Jupiter’s moon Ganymede casting its shadow on the planet in February 2022.

The Juno spacecraft, in orbit around Jupiter since 2016, has returned stunning images of Jupiter’s cloud patterns. On Sept. 11, 2019, it captured a spectacular image of Io’s shadow on Jupiter’s colorful cloud tops. On Feb. 25, 2022, Juno imaged the largest moon Ganymede’s shadow.

Saturn and beyond

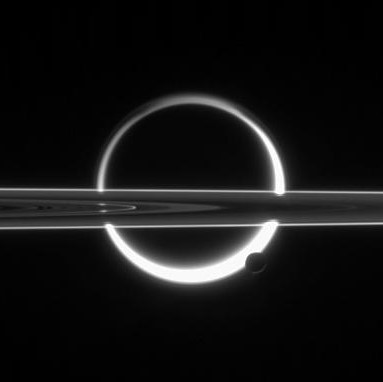

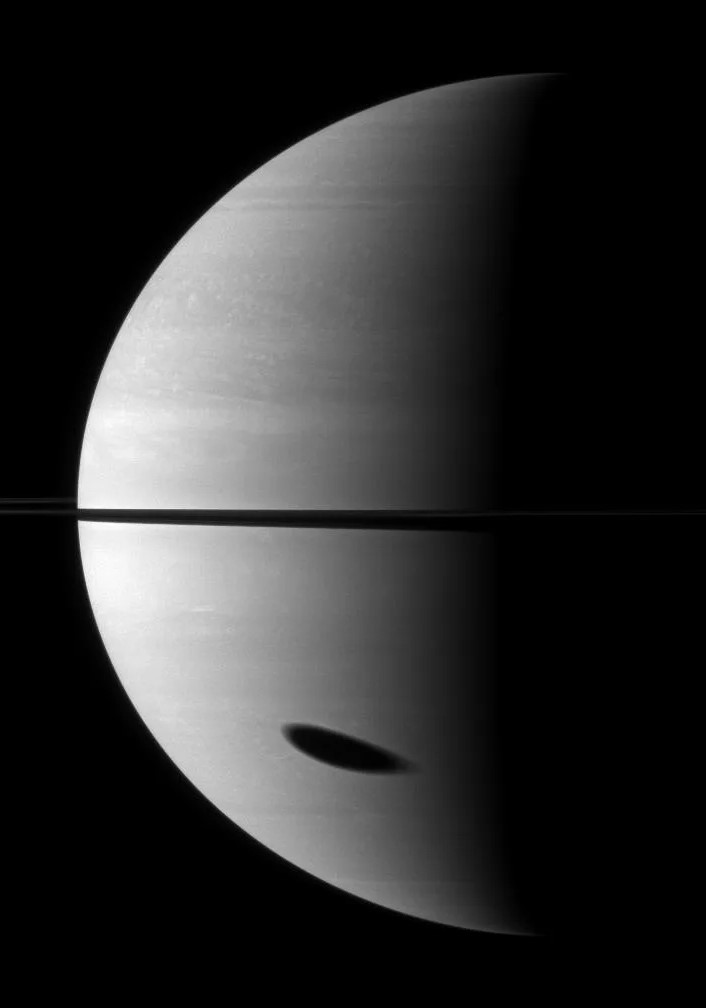

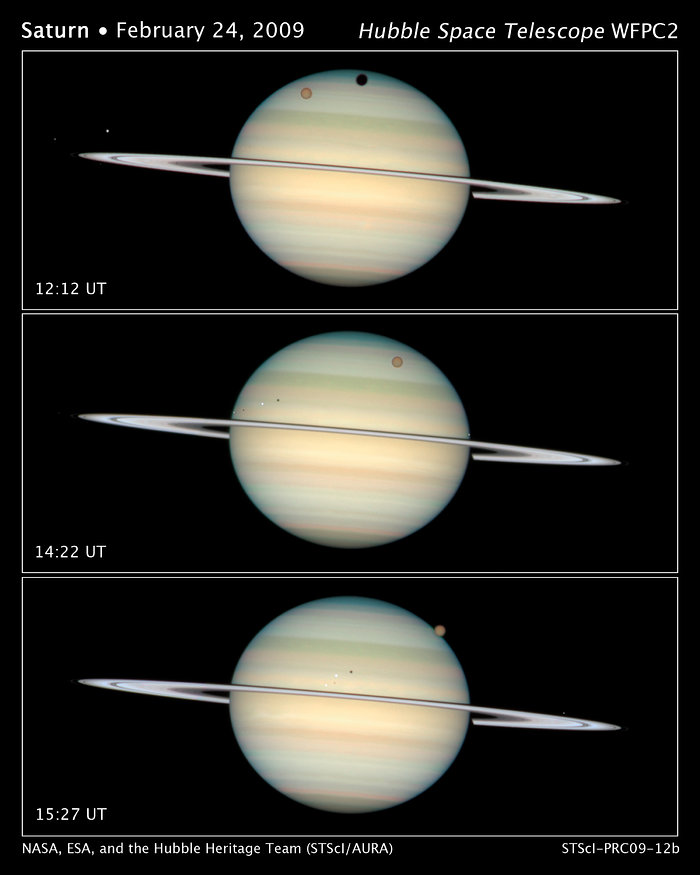

Left: As it orbited Saturn, in November 2009 Cassini imaged eclipses of moons Titan, center, and Enceladus, lower right of Titan, and the planet’s rings. Middle: Titan casts its shadow, elongated by the planet’s curvature, on Saturn in this November 2009 image from the Cassini orbiter. Right: Sequential Hubble Space Telescope February 2009 images of a quadruple eclipse, as Saturn’s moons Enceladus, Dione, Titan, and Mimas cast their shadows on the planet.

Like Jupiter, dozens of moons orbit around the ringed planet Saturn, providing ample opportunities for telescopes and spacecraft to observe them passing in front of and casting their shadows onto the planet. The Cassini spacecraft, in orbit around Saturn between 2004 and 2017, captured thousands of images of the planet, its rings, and its moons. On many occasions, Cassini passed behind the planet and its moons, creating artificial eclipses, while at other times the spacecraft imaged the moons’ shadows on the planet’s cloud tops. The Hubble Space Telescope captured a series of images of a rare quadruple eclipse on Feb. 24, 2009, as Saturn’s moons Enceladus, Dione, Titan, and Mimas transited across the planet, casting their shadows on the cloud tops.

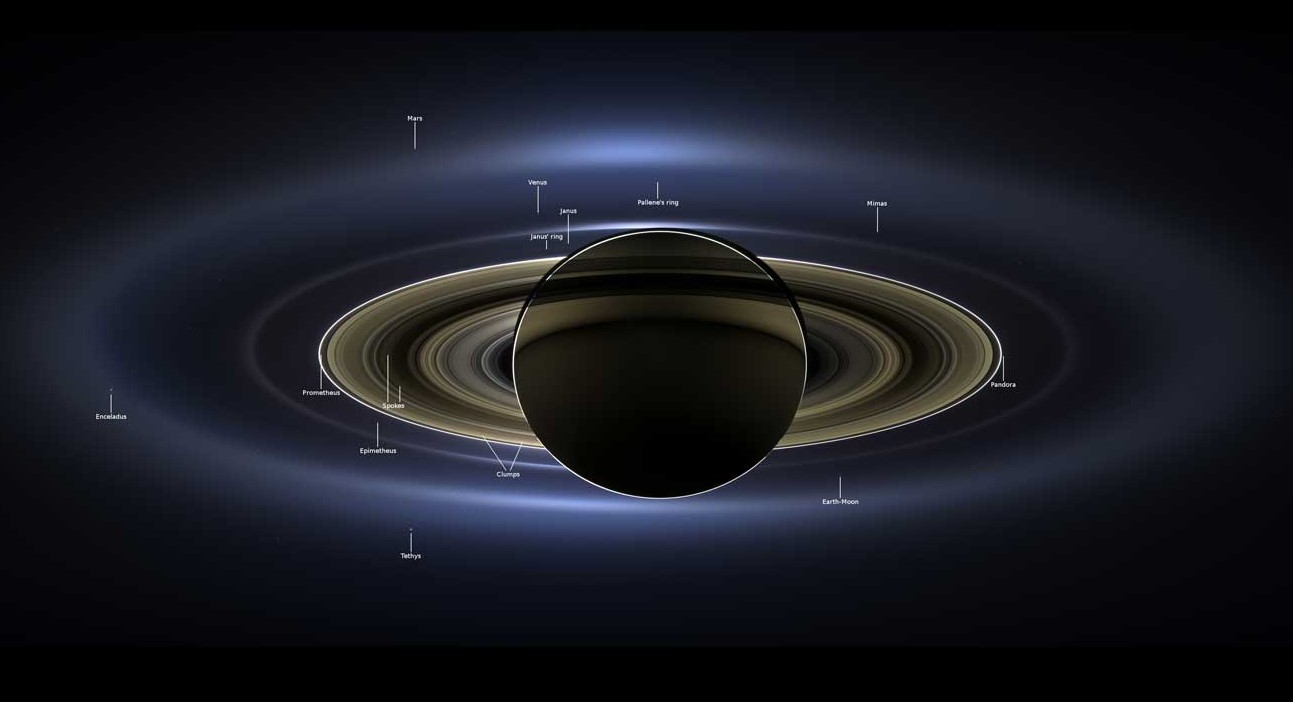

The Cassini spacecraft created this artificial eclipse of Saturn in November 2013 as it traveled beyond Saturn during one of its orbits, with many objects, including Earth, made visible.

On July 19, 2013, Cassini took a series of images from a distance of about 750,000 miles as Saturn eclipsed the Sun. In the event dubbed The Day the Earth Smiled, people on Earth received notification in advance that Cassini would be taking their picture from 900 million miles away, and were encouraged to smile at its camera. In addition to the Earth and Moon, Cassini captured Venus, Mars, and seven of Saturn’s satellites in the photograph.

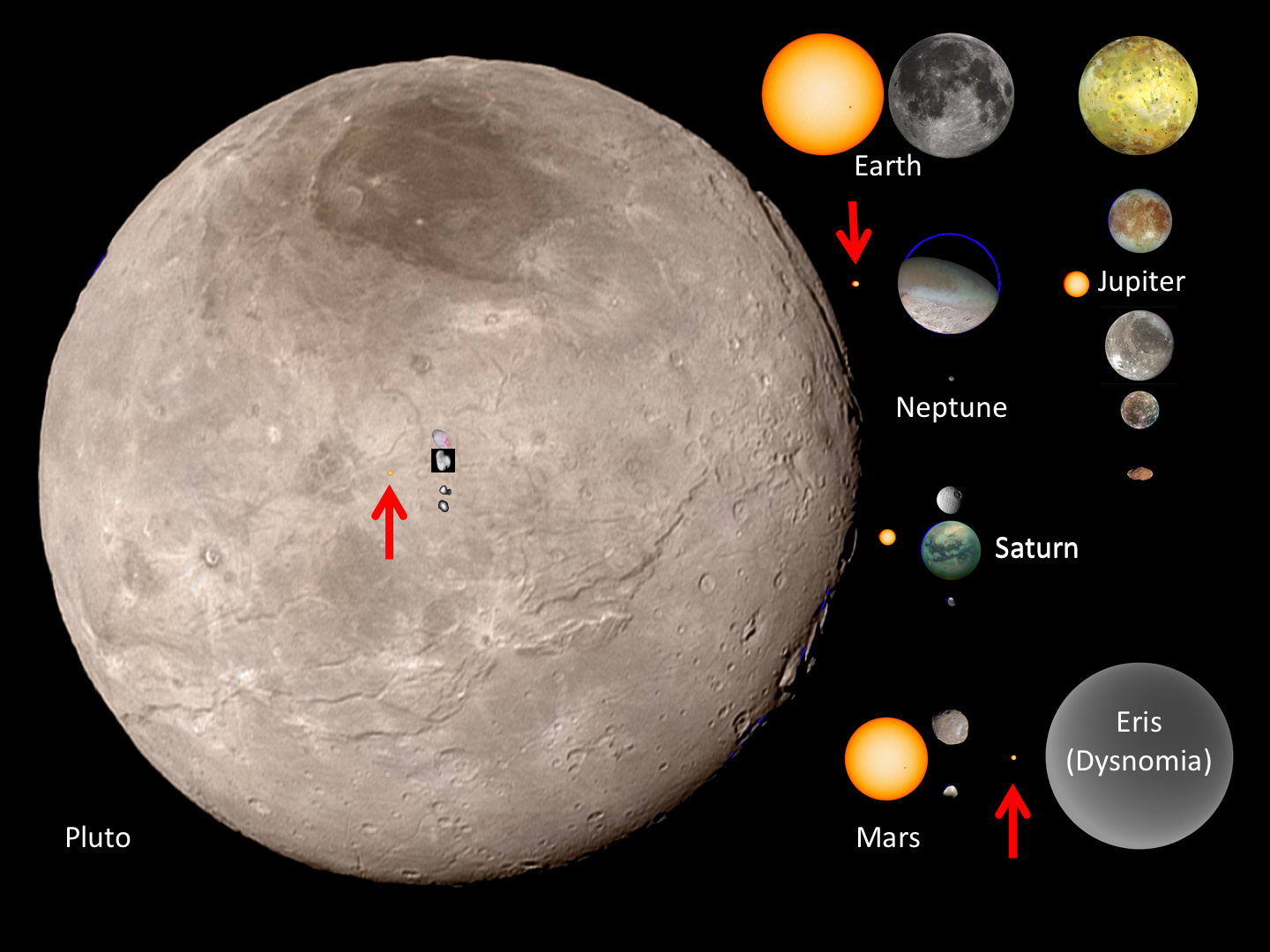

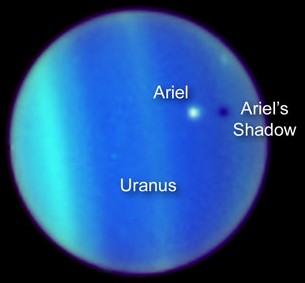

Left: Composite image showing the relative apparent sizes of the Sun and a selection of planetary moons. Image credit: courtesy sdoisgo.blogspot.com. Middle: July 2006 Hubble Space Telescope image of Uranus and its moon Ariel casting a shadow on the planet. Right: The New Horizons spacecraft created an artificial eclipse as it flew behind Pluto during its July 2015 flyby, the Sun’s rays highlighting its tenuous atmosphere.

The Earth occupies a unique position with the nearly equal apparent diameters of the Moon and the Sun, providing opportunities for annular and total solar eclipses. As viewed from planets farther in the solar system, the Sun’s apparent diameter diminishes, with the apparent sizes of the moons orbiting those planets either larger or smaller than the Sun. Eclipses as we know them do not exist elsewhere in the solar system. Spacecraft exploring those remote worlds easily create artificial eclipses by passing through the planets’ shadows, often revealing important information, such as New Horizons imaging the tenuous atmosphere surrounding Pluto.

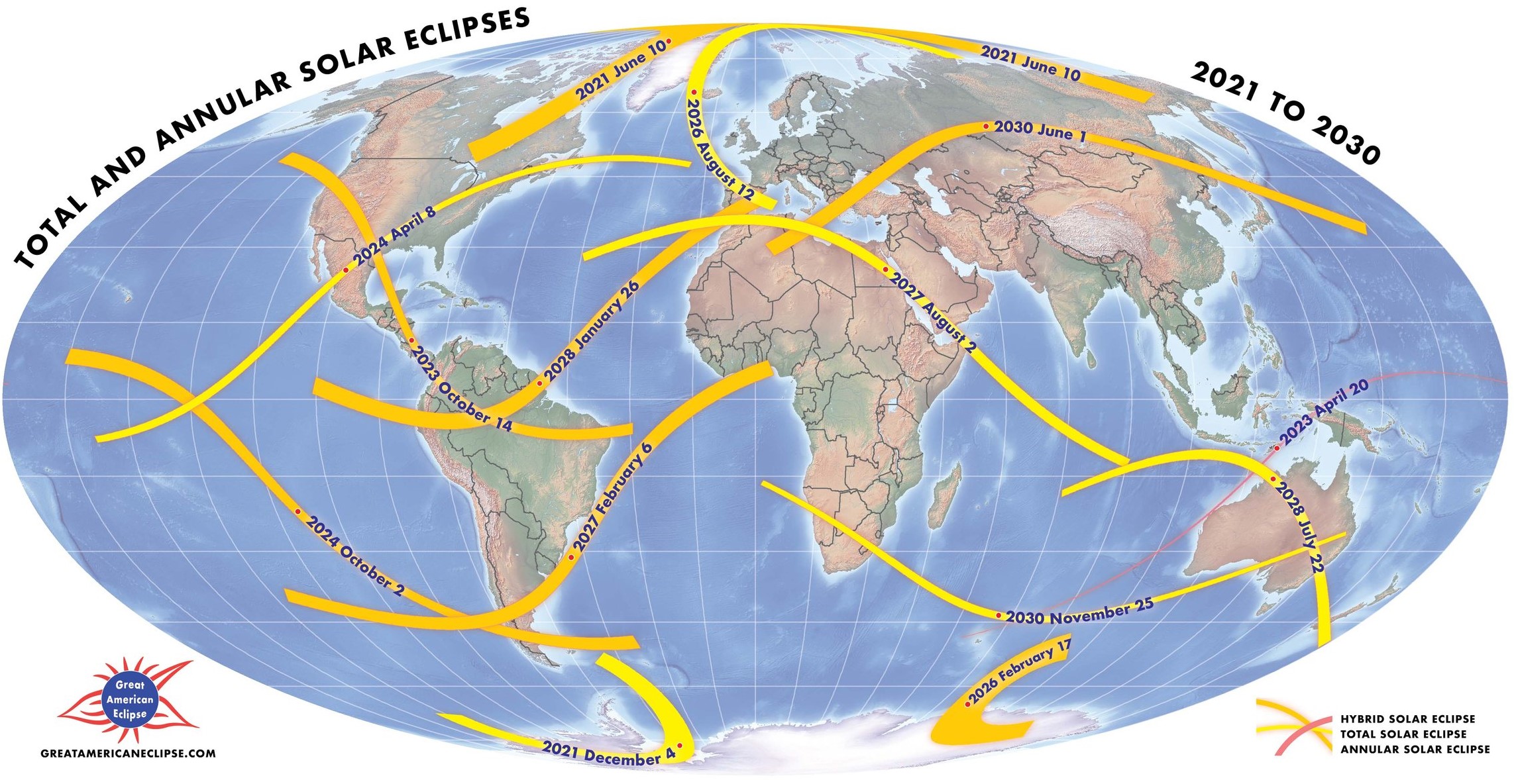

Paths of solar eclipses between 2021 and 2030. Image credit: courtesy Greatamericaneclipse.com.

The next total solar eclipse visible in North America will not occur until 2044, but over the next few years, several eclipses visible in other parts of the world will no doubt be targets of opportunity for astronauts’ cameras aboard the space station. And spacecraft exploring planets in the solar system will continue to document eclipses in those faraway places.

What's Your Reaction?

.jpg?#)