55 Years Ago: Three Months Until the Moon Landing

The rapid pace of preparations for the first Moon landing continued in April 1969. The successful Apollo 9 mission in March cleared the way for Apollo 10 to test all three components of the spacecraft in lunar orbit in May, in a dress rehearsal for the landing itself. Apollo 10 astronauts Thomas P. Stafford, John […]

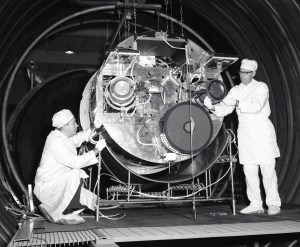

The rapid pace of preparations for the first Moon landing continued in April 1969. The successful Apollo 9 mission in March cleared the way for Apollo 10 to test all three components of the spacecraft in lunar orbit in May, in a dress rehearsal for the landing itself. Apollo 10 astronauts Thomas P. Stafford, John W. Young, and Eugene A. Cernan and their backups L. Gordon Cooper, Donn F. Eisele, and Edgar D. Mitchell continued training in spacecraft simulators while engineers prepared their Saturn V rocket and Apollo spacecraft for the mid-May launch. Preparations continued in parallel for Apollo 11, the mission to attempt the first Moon landing. The astronauts trained for the flight, including rehearsing the activities for their historic spacewalk on the lunar surface. Fulfilling President John F. Kennedy’s goal by the appointed deadline looked promising.

Apollo 10

The Apollo 10 flight plan.

Apollo 10 would serve as a dress rehearsal for the Moon landing mission. After liftoff from Launch Pad 39B – the first use of that facility – the spacecraft, still attached to the Saturn V’s S-IVB third stage, would make two revolutions around the Earth. The S-IVB would reignite for the Trans-Lunar Injection to begin the journey toward the Moon. Shortly after, the astronauts would undock the Command and Service Module (CSM) from the S-IVB, turn around, and dock with the Lunar Module (LM), tucked away in the top of the rocket stage, in a maneuver called transposition and docking. After jettisoning the S-IVB, the docked spacecraft would coast toward the Moon for about three days. The Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine would fire to drop them into orbit around the Moon. Stafford and Cernan would enter the LM and undock, leaving Young alone in the CSM. Using the LM’s Descent Propulsion System engine to lower their altitude, Stafford and Cernan would descend to about 50,000 feet above the lunar surface, and photograph the primary Apollo 11 landing site in the Sea of Tranquility. The LM would travel up to 350 miles away from the CSM during these maneuvers. The Ascent Propulsion System engine would then fire as they jettisoned the descent stage, in a simulation of a litfoff from the Moon. Stafford and Cernan would then rejoin Young in the CSM. After jettisoning the LM’s ascent stage and completing 11 more orbits around the Moon, Apollo 10 would fire its SPS engine for the retrun trip to Earth, ending with a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean. Except for the actual descent to and touchdown on the surface, Apollo 10 would follow all the steps of the actual Moon landing mission.

Left: Apollo 10 astronauts Thomas P. Stafford, left, John W. Young, and Eugene A. Cernan during a press conference at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Right: Stafford, left, Young, and Cernan hold their mission patch following a press conference at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

During two press conferences, at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida on April 8 and at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, on April 26, Stafford, Young, and Cernan discussed their eight-day mission with reporters. The trio described their upcoming flight as essentially a dress rehearsal for the Moon landing, with Stafford stating that Apollo 10 will “sort out all the unknowns and actually pave the whole way for the lunar landing mission.” They displayed their mission patch and revealed the call signs for their spacecraft – Charlie Brown for the CSM and Snoopy for the LM, after characters in the Peanuts© comic strip by Charles M. Schulz. According to Apollo Spacecraft Program Manager George M. Low, Apollo 10 would do “everything that we did on Apollo 9, only in lunar orbit.” Officials also announced that the Apollo 10 CM may carry a color TV system in addition to the standard black and white cameras. The color camera, equipped with a zoom lens, would provide live TV broadcasts from the spacecraft during critical mission operations and provide viewers at home with a glimpse of life aboard an Apollo spacecraft during a lunar mission. They also expected views of the Earth as well as the lunar landscape. During their low pass over the Moon, Stafford and Cernan would take high resolution stereo photographs of the Apollo 11 landing site. They would also activate the LM’s landing radar during the low passes, a critical test before the Moon landing. Regarding the complexity of the mission, Cernan added “I’ve never been involved in anything that has required as great an amount of coordination and team work as … to work with two vehicles in a lunar environment.”

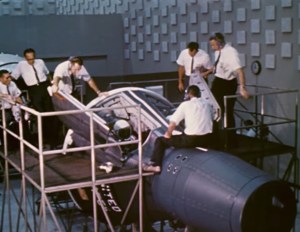

Left: Apollo 10 astronauts Eugene A. Cernan, left, and Thomas P. Stafford in the Lunar Module simulator. Right: Apollo 10 astronaut John W. Young in the Command Module simulator.

When not speaking with the press, Stafford, Cernan, and Young, as well as their backups, spent time almost daily in the LM and CSM simulators at MSC and KSC rehearsing various aspects of their upcoming mission. During many of these simulations, Mission Control in Houston was tied in for flight controllers to gain experience. The astronauts also spent time reviewing procedures, updating checklists, and receiving briefings on spacecraft systems and lunar topography.

Left: Apollo 10 astronauts John W. Young, left, Thomas P. Stafford, and Eugene A. Cernan during an inspection visit at Launch Pad 39B. Middle: Young, front, Stafford, and Cernan inspect the slide wire escape mechanism at the top of Launch Pad 39B. Right: Young, left, Stafford, and Cernan inside the blast room beneath the launch pad.

Engineers at KSC completed the Flight Readiness Test (FRT) between April 7 and 10, an activity that ensured the flight readiness of all the vehicle systems and their interaction with ground support equipment. Stafford, Cernan, and Young took part in an emergency egress drill at Launch Pad 39B, including inspecting the slide wire escape mechanism and the blast room, a concrete reinforced structure under the launch pad used in case of a catastrophic emergency during fueling of the rocket or the countdown. Managers from NASA Headquarters, KSC, MSC, and the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, met at KSC on April 23 to conduct the Flight Readiness Review for Apollo 10. At the conclusion of the meeting, during which they reviewed all aspects of the flight hardware as well as the readiness of the crew, the control centers, and the Manned Spaceflight Network, the managers decided that the mission could proceed toward a launch on May 18. On April 28, a planned power outage to conduct maintenance at KSC’s Launch Control Center also caused power outages at the launch pad, where not all systems had backup power. Workers had already loaded the rocket’s first stage with its flight load of RP-1 fuel, and the loss of power caused valves at the bottom of the tank to open, spilling 5,280 liters of fuel onto the launch pad’s flame trench. Since the fuel tank did not have any relief valves to allow air to enter the tank as fuel drained out, the loss of fluid volume caused the top of the tank to dimple inward. Quick thinking engineers at the pad instituted a work around to refill the tank and the dimple popped out with a very audible “boomp.” Launch pad manager John J. “Tip” Talone concluded of the quick action, “It worked like a champ.” Engineers resolved concern with any possible cracks in the fuel tank through non-destructive testing and visual inspections. The Countdown Demonstration Test, a final dress rehearsal of the countdown, took place between April 29 and May 6, with Stafford, Young, and Cernan participating in the final phase as if on launch day.

Left: The Apollo 10 backup crew of L. Gordon Cooper, left, Edgar D. Mitchell, and Donn F. Eisele prepare for the water egress test aboard the MV Retriever in the Gulf of Mexico. Right: Mitchell, left, Eisele, and Cooper in the life raft await pickup by a helicopter during the water egress test.

Apollo 10 backup crew members Cooper, Eisele, and Mitchell completed water egress training in the Gulf of Mexico on April 4. Using a boilerplate Apollo CM and tended by the Motorized Vessel (MV) Retriever, the astronauts practiced emerging from the capsule as if after splashdown, and with assistance from divers waited in a life raft for helicopter crews to retrieve them from the water.

Apollo 11

Left: In the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building (MSOB) at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, workers complete attaching the landing legs to the Apollo 11 Lunar Module (LM). Middle: In the MSOB, workers lower the Command Service Module onto the Spacecraft LM Adaptor. Right: In KSC’s Vehicle Assembly Building, workers lower the Apollo 11 spacecraft onto its Saturn V rocket.

As launch day neared for Apollo 10, work progressed to get Apollo 11 ready for its historic mission. In KSC’s Manned Spacecraft Operations Building (MSOB), workers attached the four landing legs to the Apollo 11 LM, mated it with its Spacecraft LM Adapter (SLA) on April 4, and three days later completed assembly of the spacecraft by adding the CSM. On April 14, they transported the spacecraft to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB), where engineers stacked it atop its Saturn V rocket. They performed tests on the vehicle prior to its rollout to the launch pad in mid-May.

Left: Apollo 11 astronaut Neil A. Armstrong practices taking the first step onto the lunar surface. Middle: Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, left, and Armstrong train for lunar surface activities. Right: Aldrin trains to carry the science instruments.

The Apollo 11 prime crew of Neil A. Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin and their backups James A. Lovell, William A. Anders, and Fred W. Haise busied themselves training for the Moon landing. On April 14, Apollo Spacecraft Program Manager Low announced in a press conference that Armstrong would most likely be the first person to exit the LM and take humanity’s first steps on the lunar surface. Aldrin would follow about 20 minutes later. The LM cabin’s configuration primarily dictated the rationale for this decision – because of the way the LM’s hatch opened inward, it would be difficult at best for Aldrin to exit first, since he would need to climb over Armstrong in the cramped quarters of the cabin, both of them wearing bulky spacesuits.

Left: Apollo 11 astronaut Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin tests his spacesuit in a vacuum chamber. Middle: Michael Collins prepares to enter the centrifuge gondola. Right: Neil A. Armstrong trains with a lunar sample container in a vacuum chamber.

To ensure the space-worthiness of their spacesuits, the astronauts tested them in the 8-foot altitude chamber in MSC’s Crew Systems Division. Collins and Anders spent time in the centrifuge in MSC’s Flight Acceleration Facility, practicing profiles of a launch and a reentry from a lunar mission. In MSC’s Building 9, on April 18 Armstrong and Aldrin, wearing their spacesuits, completed a 2.5-hour simulation of activities, such as collecting rock and soil samples and deploying scientific instruments, that they will perform on the lunar surface. Armstrong, Aldrin, Lovell, and Haise each completed sea-level runs in Chamber B of MSC’s Space Environment Simulation Laboratory. During these tests, the astronauts wore their spacesuits and practiced the various lunar surface activities, such as activating the television camera, collecting rock samples, and deploying the scientific experiments of the Early Apollo Surface Experiment Package (EASEP). They followed up these ambient sessions with altitude runs in early May.

Left: One of the three Lunar Module-2 drop tests conducted during the first week of April. Right: The Lunar Receiving Laboratory for astronauts and lunar samples returning from the Moon.

To certify the LM and its systems for the loads it would encounter during a lunar landing, engineers at MSC continued drop tests with the flight-like LM-2 in the Vibration and Acoustics Test Facility (VATF). Beginning the series in late March, engineers completed three of the five drop tests in early April. These tests induced lateral accelerations on the wire harnesses and plumbing in the spacecraft’s aft equipment bay, produced high acceleration loads around the inertial measurement unit and the environmental control system, and stressed the LM’s front face and side hatch. The final test in early May completed the certification of the LM for the first lunar landing. Elsewhere at MSC, staff continued to prepare the Lunar Receiving Laboratory (LRL) for the return of astronauts and samples from the Moon. Workers completed long-duration simulations of the LRL’s major functions including the Crew Reception Area in early April. The tests highlighted some deficiencies requiring correction prior to the first Moon landing flight. These included problems with the sterilization equipment and the gloves used in gloveboxes to handle lunar samples repeatedly developed holes, compromising the biological barrier. A management readiness review held April 17-18 also noted these as areas needing improvement. To solve these issues, MSC Director Robert R. Gilruth named his special assistant Richard S. Johnston to oversee all aspects of the LRL. Workers corrected the problems and the LRL received certification just prior to the Apollo 11 mission.

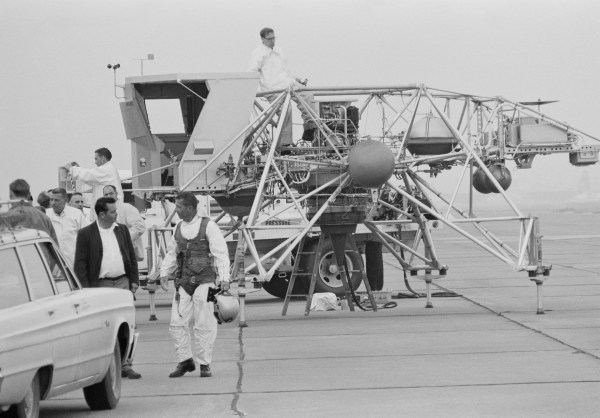

Left: At Ellington Air Force Base in Houston, NASA pilot Harold E. “Bud” Ream at the controls of Lunar Landing Training Vehicle-2 (LLTV-2) on its first flight after flights resumed. Middle: Ream walks away from LLTV-2 after the successful flight. Right: Multiple exposure of a practice landing at the Lunar Landing Research Facility at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia.

At Ellington Air Force Base near MSC, the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV) resumed flight operations on April 7 with MSC pilot Harold E. “Bud” Ream at the controls. Apollo commanders relied on the LLTV as a key training tool to simulate the flying characteristics of the LM, especially of the final 500 feet of the descent. But NASA managers had grounded the LLTV after a crash in December 1968, and following investigations had allowed flights to resume but only by test pilots. Ream completed more than a dozen flights before managers cleared the LLTV for astronaut training in June. While the LLTV remained grounded, Apollo 11 astronauts made use of the Lunar Landing Research Facility (LLRF) at the NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, to train for the final descent to the lunar surface. Lovell and Haise practiced Moon landings in the LLRF in mid-April. Armstrong and Aldrin would use the facility for practice landings in late June. Once managers cleared the LLTV for astronaut use in early June, Armstrong and Lovell completed training flights in that higher fidelity vehicle later that month.

Apollo 12

Looking beyond Apollo 11, NASA continued preparations for the next missions. In case Apollo 11 could not achieve the Moon landing, the agency established readiness dates for Apollo 12 of Sept. 13 and Apollo 13 of Nov. 10, to try again. If Apollo 11 succeeded, the follow on missions would occur at four-month intervals and explore different regions of the Moon with an expanded set of science instruments and geology objectives.

Left: Apollo 12 astronauts Charles “Pete” Conrad, left, Richard F. Gordon, and Alan L. Bean pose in front of a boilerplate Apollo capsule during water egress training when they served as the backup crew for Apollo 9. Right: Apollo 12 prime crew members Conrad, left, and Bean, right, review Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package equipment as backup astronaut James B. Irwin, with arms folded, looks on.

On April 10, NASA announced the prime and backup crews for Apollo 12. The prime crew consisted of Charles “Pete” Conrad, Richard F. Gordon, and Alan L. Bean. The three had served as the backup crew for the March 1969 Apollo 9 mission. Conrad had flown in space twice before, during the then record-breaking eight-day Gemini V mission in 1965 and with Gordon on his only previous mission during Gemini XI in 1966, when they achieved a then-record human space flight altitude of 853 miles. NASA selected Bean, a spaceflight rookie, in 1963. The Apollo 12 backup crew of David R. Scott, Alfred M. Worden, and James B. Irwin would fly the mission in case something happened to the prime crew. Scott had previously flown in space aboard Gemini VIII in 1966, the mission that accomplished the first docking in space and also made the first emergency landing, and more recently he flew aboard Apollo 9. Worden and Irwin had not yet flown in space, but Worden had served on support crews and Irwin as the commander of the crew that conducted tests with LM Test Article-8 (LTA-8) in 1968 to evaluate the LM in a vacuum chamber at MSC.

Left: At NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, workers unwrap the Apollo 12 Lunar Module (LM) descent stage shortly after its arrival in the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building. Middle: Workers lower the Apollo 12 LM ascent stage onto the Command Module for a docking test. Right: Workers roll the Apollo 12 Saturn V S-II second stage into KSC’s Vehicle Assembly Building.

At KSC, components for Apollo 12 began to arrive for processing. The Saturn V’s S-IVB third stage had arrived at the VAB in March, joined by the S-II second stage on April 21, with the S-IC first stage expected in May. The Apollo 12 LM and CSM had arrived in the MSOB in March, and as workers finished up work with the Apollo 11 spacecraft, they shifted their focus to processing Apollo 12. On April 18, they conducted a docking test between the LM’s ascent stage and the CSM, already placed in its altitude chamber for future testing.

To be continued …

News from around the world in April 1969:

April 1 – At MSC, Director of Engineering Maxime A. Faget displayed a wood and paper model of a concept that would develop into the reusable space shuttle.

April 1 – The Hawker-Siddeley Harrier – a vertical take-off and landing fighter jet – began service with the Royal Air Force.

April 4 – Surgeon Dr. Denton Cooley implanted the first temporary artificial heart in a human in an operation at St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital in Houston.

April 7 – First use of what became the Internet, with circulation of a Request for Comments document among the Network Working Group developing communications protocols for the ARPANET, the Internet’s forerunner.

April 14 – The Montreal Expos beat the visiting St. Louis Cardinals in the first Major League Baseball game played outside the U.S.

April 20 – Princeton University announced that for the first time in its 223- year history it would admit women starting in the fall of 1969.

April 22 – Robin Knox-Johnson completed the first solo sail around the world without stopping or taking on supplies during the entire 312-day voyage.

April 28 – Charles de Gaulle resigned as president of France after 11 years in office.

April 29 – President Richard M. Nixon awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom to bandleader Duke Ellington.

What's Your Reaction?

.jpg?#)